China uses border issue as tool to build pressure on India

As India and China are engaged in a stand-off in the Galwan Valley,

Maj Gen GG Dwivedi (retd) shares his insight into the current situation. He has commanded 16 JAT in Siachen (Durbuk Pangong Tso area), a brigade in the Kashmir Valley and Mountain Division in the North East and also served as India’s defence attaché in China and North Korea from 1997 to 99. He is currently a professor of strategic and global affairs.

China considers it opportune to push its agenda regarding disputed areas as the world is battling the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, President Xi Jinping is under pressure due to slowing down of the Chinese economy. Also, China does not want India to develop infrastructure in Ladakh. —Maj Gen GG Dwivedi (retd)

Can you explain the difference between the LoC and the LAC?

A: There is a tendency to compare the Line of Control (LoC) and the Line of Actual Control (LAC) but these are two distinct terms. We have International Border and LOC with Pakistan and LAC with China in Jammu and Kashmir. LoC is like a de facto border and manned by troops deployed on the either side. In contrast, LAC is neither delineated nor demarcated. It is based roughly on the positions held by both sides towards the end of 1962 war. As a result, both sides have their own interpretation. In the Ladakh region, it generally corresponds with the Chinese claim line as China captured most of the Aksai Chin area in the 1962 war. However, there are a number of contested points where the two sides have a varying perception. In the middle sector and eastern sector (Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh), the LAC is by and large aligned with the McMahon Line.

Can you give a brief overview of the border issue between India and China?

Though no official boundary has been negotiated between India and China, the Indian Government considers a line similar to the Johnson Line of 1865 as the boundary, according to which Aksai Chin is a part of India. The Chinese Government, however, considers a line similar to the McCartney-MacDonald Line of 1899 as the boundary which is well to the west of Johnson Line. The 1913-14 Shimla Convention between Great Britain, China and Tibet defined the boundary between Tibet and British India, which later came to be known as McMahon Line. But China declined to sign it. After China annexed Tibet in 1951, the two countries started sharing boundary. China initially did not raise the border issue as surreptitiously it was constructing a highway from Kashgarh in Xinjiang to Lhasa in Tibet in the 1950s which passed through Aksai Chin. When India learnt of this in 1959, it raised the matter with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This is how the border problem started, ultimately leading to the 1962 Indo-China war. Incidentally, the opening shots of the war were fired from the Galwan Valley.

Why do you think that the LAC has not been defined as yet?

Chinese has kept dragging their feet on the issue as it is not in their interest to resolve the boundary imbroglio. The PRC has often used the border issue as a tool to build pressure on India.

Why has China created the trouble amid the pandemic?

China is known for creating problems when it is confronted with internal and external issues. At present, China considers it opportune to push its agenda regarding disputed areas with Taiwan, South China Sea and the LAC, as the world is battling the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, President Xi Jinping is under pressure due to slowing down of the Chinese economy and a global outcry holding China responsible for the pandemic. Also, China does not want India to develop infrastructure in Ladakh as presently they have a definite edge over us. The Galwan Valley is important because from there, China can dominate Durbuk- Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) road that India constructed recently. China also has high stakes in the Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir (POK), too, as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor traverses through the region. It has also invested in various projects in the POK, including the proposed $9 billion Daimer-Bhasha Dam.

What are the options before India in present situation?

Our aim is to restore the status quo ante that existed in April which implies that the PLA has to pull back. To ensure this, adequate pressure has to be built on China through various means, including military, political, diplomatic and economic

Why has not the Chinese media reported on casualties suffered by their troops?

China has an authoritarian rule and a state-controlled media. The communist leadership employs media as an instrument to spread its propaganda and fight an information war.

An Expert Explains: Deciphering the dynamics of de-escalation in eastern Ladakh

Written by Maj Gen (retd) Prof G G Dwivedi , Edited by Explained Desk

The process of de-escalation has been underway for several days in eastern Ladakh, where Chinese forces made large scale incursions in the areas of Pangong Tso, Galwan and Depsang in May. Prompt counter-deployment by the Indian Army to check the Chinese intrusions resulted in a serious standoff, marked by violent clashes on June 15.

There is lack of clarity in the environment about de-escalation per se; as terms like disengagement, pulling back, and withdrawal are being used concurrently, in the same breath.

De-escalation is a complex and time consuming exercise, as it entails navigating an uncharted course in a graduated manner. To decipher the dynamics of the ongoing de-escalation on the Line of Actual Control (LAC), it is essential to comprehend the genesis of the Sino-Indian border dispute, and the typical ‘conflict cycle’.

While the main reason for the Sino-Indian conflict is apparently the unsettled border issue, there are other factors too – including divergent geopolitical interests and ideological dimensions.

In Ladakh, India considered the border to be along the Johnson Line of 1865, which included Aksai Chin. The Chinese on the other hand, initially agreed to the Macartney-MacDonald (M-M) line of 1899, which was west of the Johnson Line.

Towards 1959, the Chinese began to establish a series of posts west of the M-M Line, usurping large parts of Aksai Chin, as they had constructed the Western Highway from Kashgar to Lhasa through it, and wanted to consolidate the hold on Tibet. In response, India adopted a forward policy by setting up posts opposite the Chinese to check the latter’s expansion.

In 1960, the Chinese came out with a map laying claim to almost the whole of Aksai Chin. The main reason why Mao went for war in 1962 was to capture the claimed territories in eastern Ladakh, as also to teach India a lesson.

During the 1962 war too, DBO, Galwan, and the Pangong Tso-Chushul areas were scenes of major action. By the time the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire, the PLA had almost secured the areas up to the 1960 claim line. At the end of the war, the two sides as per mutual understanding withdrew 20 km from the positions last held by the opposing forces.

Subsequently, the Line of Actual Control came to denote the line up to which the troops on the two sides actually exercised control. However, the LAC was neither delineated on the map nor demarcated on the ground. Hence, both India and China have different perceptions on the alignment of LAC.

However, over a period of time, Patrolling Points (PPs) were identified on the ground, setting the limits up to which the two sides could patrol. These PPs became reference points, although these are not bang on the LAC but at some distance on the home side. Hence, it is through patrolling boundaries that the Indian and Chinese troops assert their territorial claims. There were 23 areas which were contested by both sides.

Also read | Ladakh through a bifocal lens: a short zoom-in, zoom-out history

Given the potential for clashes, five major agreements were signed between India and China to ensure peace on the border.

* The first one on ‘Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity along the LAC’ was signed in 1993, which formed the basis for the subsequent agreements.

* In 1996, a follow-up agreement on ‘Confidence Building Measures’ along the LAC was inked, denouncing use of force or engaging in hostile activities.

* In the 2005 Agreement, ‘standard operating procedures’ were laid down to obviate patrol clashes.

* The Agreement of 2012 set out a process for consultation and cooperation.

* The ‘Border Defence Cooperation Agreement’ was signed in 2013 as a sequel to the Depsang intrusion by the PLA. Its emphasis was on enhancing border cooperation and exercising maximum restraint in case of ‘face-to-face’ situations. Wherever there was a difference of perceptions in disputed areas termed as ‘grey zones’, both sides could patrol up to the perceived line, but were not to undertake any build-up.

The dynamics of de-escalation

In the Chinese strategic culture, the use of force is considered perfectly legitimate. Since 1949, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has repeatedly resorted to force against neighbouring countries in the pursuit of its expansionist design.

It was in Chinese interest to not define the LAC or resolve the border dispute, so as to use it as leverage against India. The Chinese policy was to keep consolidating its position by building infrastructure, alongside the pursuit of the policy of ‘nibbling and negotiating’ to make tactical gains, employing unconventional means such as using graziers and border militias.

Given the scope and scale, the PLA aggression was well planned, and definitely cleared by the Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest defence body in the Chinese system. In the process, the Chinese violated all of the above agreements, and once again betrayed India’s trust.

Beijing’s strategic aim apparently was to convey a strong message to New Delhi to kowtow to its interests, and to desist from building border infrastructure so as to maintain status quo, which is at present in China’s favour.

In tactical terms, it was to make limited gains through large scale intrusions, undertake a build-up in the grey zones, and seek to shift the alignment of the LAC further westward.

The PLA’s probable objectives in the Pangong Tso area was to dominate the Chushul Bowl; in Galwan to dominate the Durbuk-DBO road; and in DBO, to posture towards the Depsang plateau to pose a threat to Siachen from the east and ensure the security of the Western Highway.

Given India’s strong resolve both at the political and military levels alongside favourable world opinion, the Chinese decided to de-escalate, having achieved their initial aim and to obviate further upsurge.

Decoding LAC Conflict

- China common worry, India and US step up military, intel ties

- LAC: No more thinning of troops, Army prepares for the long haul

- OPINION | India must formally revive Quad, seek its expansion

The process of de-escalation

Every conflict has a cycle – it begins with escalation, and is followed by contact, stalemate, de-escalation, resolution, peace-building and reconciliation.

The de-escalation process entails talks at multiple levels, and ground action in various stages. As in this case, there have been three rounds of talks at the Corps Commander level, simultaneous talks between Joint Secretaries, and at the level of Special Representatives.

On the ground, the first step in the de-escalation process is of disengagement – i.e., to break the ‘eyeball-to-eyeball’ contact between the opposing troops on the forward line by pulling back to create a buffer zone. This is currently in progress – the forward troops on both sides are reported to have pulled back by about 1.5 km in the area of PP 14 in Galwan, PP 15 southeast of Galwan Valley, and PP 17A in the Gogra-Hot Spring areas. Similar action will be required to be taken in the Pangong Tso fingers area, where the PLA has reportedly intruded up to Finger 4, as also in the PP 10-11 areas in Depsang-DBO.

The next step is the pulling back of the troops in the immediate depth, followed by reserve formations in the rear.

📢 Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

In the present case, the PLA created a number of intermediate positions, besides staging forward 4 Motorised and 6 Mechanized Divisions. Even fighter aircraft have been positioned at the forward air bases like Ngari and Hotan. India too, has undertaken the requisite build-up. Withdrawal of all these elements will require many more rounds of talks at various levels.

Given the serious trust deficit — as the PLA is known to backtrack — each move will need to be confirmed and verified on the ground, and complemented by other surveillance means. Even the distance of pulling back cannot be sacrosanct, as the PLA is in a better position to build up, given the terrain advantage and better infrastructure.

India’s bottom line at the negotiation table is to restore the April 20 status quo ante. The Chinese are masters at engaging in marathon talks. Maj Gen Liu Lin, commander of the South Xinjiang Military Region (SXMR), who is currently representing the PLA in the Corps Commander-level talks, has been in the area as Division Commander and Deputy of SXMR. He took over the SXMR last year, and will be around for a couple of years, given the PLA’s long command tenures.

Soldiers keep guard as an Indian Army convoy moves on the Srinagar-Ladakh highway at Gagangeer, north-east of Srinagar. (AP Photo)

Well aware of the ground situation, Liu can be expected to indulge in hard bargaining. Therefore, the de-escalation process is set to be in for a long haul, marked by the ‘going back and forth’ phenomenon. India must have its options in place, should the process of de-escalation get stalled.

Maj Gen (Dr) G G Dwivedi: ‘Right now, Chinese have an edge, we must neutralise it’

Maj Gen (Dr) G G Dwivedi, who commanded a Jat battalion in this sector in 1992, and was subsequently the defence attaché to China in 1997, told The Indian Express over the phone that he is not surprised by the recent Chinese belligerence.

The peaks around the Galwan valley last saw bloodshed in 1962, when Chinese soldiers opened fire on a company of 5 Jat on October 22, killing 36 soldiers and capturing company commander Major S S Hasabnis. It marked the start of the 1962 war.

“It is part of China’s ‘nibble and negotiate policy’. Their grand aim is to ensure that India does not build infrastructure along the LAC, change the status of Ladakh, cosy up to the US and join the anti-China chorus caused by Covid-19. It is their way of attaining a political goal with military might, while gaining more territory in the process.’’

Dwivedi recounted the time he commanded 16 Jat in Pangong Tso and Hot Springs area in 1992. There was no tension between the two countries at that point. “We used to patrol up till Hot Springs and so did they. The Ladakh Scouts controlled the Galwan valley and did not encounter any problems either. We would learn of Chinese patrols from the red Hong Mei cigarette packets they left behind and graffiti on the rocks that read ‘Chung ko (This is China)’.” Dwivedi said the Indian troops would retaliate by scribbling ‘This is India’ on the rocks.

Things have changed, and Beijing is worried about India’s recent actions of reorganising Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh and improving infrastructure in the region, Dwivedi said. “It has high stakes in PoK as the $60-billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) traverses through it, and it is also the site of the proposed $9 billion Diamer Bhasha Dam, a joint project of China and Pakistan.’’

He said that China’s current aggressive behaviour also coincides with pressure on President Xi Jinping, who is the chairperson of the Central Military Commission, due to opposition around the globe due to Covid-19 and the economic slowdown at home.

The PLA’s aim, said Dwivedi, is to dominate Durbuk-DBO road, strengthen its position in the Fingers area, halt the construction of link roads in Galwan-Pangong Tso and negotiate de-escalation on its terms.

“They have quietly and steadily built a lot of infrastructure along the LAC, and now they want to dominate the hilltops. Any military man will tell you that this matters because if you don’t occupy the hilltops, you are like a sitting partridge.’’

Decoding LAC Conflict

- Galwan faceoff: How serious is the situation, and what happens next?

- China, the Line of Actual Control and India’s Strategic Situation

- Growing power differential is what lies behind China’s assertion in Ladakh

On the way forward, Dwivedi said India must be firm on restoration of status quo as on April 30. “We must be firm on that, they should go back. We started to disengage but the Chinese did not, they want to consolidate their gains and make us accept the new LAC alignment.”

Negotiations depend on how strong you are on the ground. “Right now, the Chinese have an edge, we must neutralise it. We must either push them back or occupy some other place that affects them.”

Military action, said Dwivedi, should be accompanied by political, diplomatic and economic action. “We must isolate China in the geo-political arena and ensure a consensus in our favour. Last but not the least, let us present a united front as a nation and win the propaganda war as well.”

India-China: Reimagining ‘New Era of Cooperation’ Strategic Imperatives

Published in USI journal on October 2019 – December 2019

Abstract

Given the divergent national interests and complex outstanding issues between India and China, ‘one on one’ informal summits format adopted by PM Modi and President Xi has definitely contributed towards keeping the bilateral relations on track. The first such summit was held at Wuhan in China on 27-28 April 2018. Its key outcome was putting in place a process of bilateralism to facilitate strategic communication at the highest level and building mutual trust – ‘wuhan Spirit’. The summit also sought to provide ‘strategic guidance’ to the respective militaries to enhance cooperation for effective border management.

The second summit was held on 11-12 October 2019 at Mamallapuram, with focus on restoration of ‘Wuhan Spirit’, revamping the process of strategic communication and lending impetus to the mechanism of strategic guidance. President Xi laid down ‘100 year plan’ to rejuvenate the relations between two neighbours, signifying incremental approach to narrow the existing divide. He made six specific proposals seeking both sides to correctly view each other’s development and enhance mutual trust.

Relations between Delhi and Beijing transcend bilateral bounds and have strategic significance with far reaching ramifications. Real challenge for the two is to keep contentious issues at bay and yet, enlarge the area of cooperation. Informal dialogue between the top leaders offers an excellent platform to this end. While reimagining ‘new era of cooperation’, India must be forth right in safeguarding its national objectives as Chinese are ardent practitioners of realpolitik.

Introduction

Prime Minister Modi and President Xi Jinping, the two powerful leaders, engaging each other at informal ‘one on one’ summits to reinvigorate India-China ties has set a new norm of freewheeling dialogue. The venue of first informal summit, held on 27-28 April 2018, was Wuhan; a historical city where unrest to unseat the last imperial.

Qing Dynasty started in 1911. The main outcome of this summit was setting up a process of bilateralism and building mutual trust – ‘Wuhan Spirit’. The second informal summit was held after one and half years, on 11-12 October 2019 at Mamallapuram, again a city of historic significance. The thrust was to consolidate upon the gains of the previous summit and explore new avenues of cooperation. The third informal summit is slated to take place in China sometime during next year, for which Mr Xi extended the invite to Mr Modi when the two met during the recently concluded BRICS Summit in Brazil.1

Given the diverse cultures, divergent national interests and complexities of outstanding issues between the two giant neighbours, innovative format of informal dialogue has certainly contributed towards keeping the bilateral relations on track. The mechanism of strategic guidance and its implementation on the ground by the two sides obviated differences from turning into disputes. As the rising powers, scope of relations between Delhi and Beijing transcends the bilateral bounds as these have strategic significance with far reaching global implications. This article undertakes an in depth review of the Mamallapuram Summit and prospects of reimagining ‘new era of cooperation’ in the times ahead.

Wuhan to Mamallapuram: Reimagining ‘New Era of Cooperation’

Circumstances which led to the Wuhan Summit could be largely attributed to the outcome of strategic review undertaken by President Xi to further his ‘China Dream’ (Zhong Meng) which envisions ‘prosperous and powerful China’- a ‘great modern Socialist Country’ by mid of the century.2 People’s Republic of China (PRC) has always opposed the global security system based on American alliances and partnerships. Beijing is earnestly pursuing its grand design of shaping China centric world order. To this end, China has undertaken series of initiatives to set up alternate multilateral structures including Shanghai Corporation Organisation (SCO), Asia Infrastructure Development Bank (AIDB) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China’s future global architecture envisages bipolar world and unipolar Asia. As per Xi’s strategic calculus, in the coming decades while China and USA will be the competing powers, India and Japan will be other important players, both in its neighbourhood. Throughout its history, China has coerced her neighbours to acquiesce; it prospered when the emperor was strong and periphery was peaceful. Conducive periphery, therefore, is vital for PRC to pursue its grand design. Hence, passive Japan alongside marginalised India lacking in capability and political will to pose any challenge to China suits Communist leadership. Beijing is also fundamentally opposed to the very idea of ‘Indo-Pacific’. It is inimical to Quad (America, Japan, Australia, and India grouping), and at no cost will condescend to the idea gaining currency. In the ancient times, its emperors dealt with the adversaries by pitching ‘one barbarian against the other’.3 Doklam stand-off in 2017 also acted as a trigger for China to review its India policy.

From Indian perspective too, definite need was felt to recast China policy in the wake of fast changing global geo political milieu, necessitating rebalancing of relationship. Incremental process and sustained dialogue has been the main feature of engagement between Delhi and Beijing since the past four decades. It is astute diplomatic initiative to leverage ‘Modi-Xi’ personal chemistry so as to reduce prevailing tension and explore new vistas of cooperation through informal meetings.

Significant outcome of ‘Wuhan Summit’ was to reset bilateral relations through periodic dialogue between the top leadership and facilitate ‘strategic communication’ at the highest level. Concurrently, it also sought to provide ‘strategic guidance’ to the respective militaries, facilitate building mutual trust and understanding, so as to enhance cooperation for effective management of borders. Agreement to work jointly on an economic project in Afghanistan was an important initiative, which could be a future format for such cooperation in the third country.

The second informal summit was held on 11-12 October 2019 at Mamallapuram, an ancient township which had trade and cultural links with Chinese Guangzhou port city during Pallava – Tang Dynasties, during latter half of first millennium.4 Eighteen months period between the two informal summits was buffeted by numerous irritants. Beijing’s deepening relations with Islamabad coupled with its statements related to Kashmir, signifying change in its policy, were major dampeners. China continued with routine incursions by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). On trade also, where India has deficit of around US $ 53 bn, China continued to play hardball.

Mamallapuram Summit, although formally announced at the eleventh hour, was indicative of restoring the ‘Wuhan Spirit’. Main focus of the informal dialogue was on consolidation and revamping the process of strategic communication, as also providing impetus to the mechanism of strategic guidance. There was earnest effort on both sides to rebalance the bilateral ties. The contentious issues, like the Jammu and Kashmir and military exercise ‘Him Vijay’ in Arunachal Pradesh, were off the table. There was a clear message about the intent of two leaders to maintain high level engagement process and, as responsible powers, resolve the existing differences through dialogue.

In consonance with the Chinese sense of time wherein hands of clock tick by centuries and decades, President Xi laid down a ‘100 year plan’ to rejuvenate the relations between the two neighbours. “We must hold the rudder and steer the course of China India relations”, stated Xi.5 It signified a balanced and incremental approach over a prolonged period to narrow the existing divide and overcome trust deficit. President Xi made six specific proposals which in essence seek both sides to correctly view each other’s development and enhance mutual trust to gradually improve understanding from a long term perspective.6 While strategic communication will ensure proper handling of sensitive issues, improved exchanges of military and security personnel will dispel doubts. The proposals also suggest increased ‘people to people’ contact and enhanced cooperation between two countries in the international, regional and multi-lateral forums.

Strategic Imperatives

President Xi ranks among the most powerful world leaders of the day. His squeezing time for informal meetings, in a heavily packed diplomatic calendar, may appear to be a rare phenomenon; yet, there is a sound rationale behind it. Xi has jettisoned the collective leadership model and amended the constitution to become the life-long President.7 Therefore, he is well aware that the onus of China’s rejuvenation and its emergence as superpower rests entirely on him. In case he fails to succeed, China could plunge into chaos.

PRC’s core national objectives are ‘stability, sovereignty and modernity’.8 While ‘stability’ implies unchallenged authority of Communist Party of China (CPC), ‘sovereignty’, besides strategic autonomy, entails unification of all claimed territories with motherland, which includes Taiwan, disputed islands in East and South China Sea besides Arunachal Pradesh (Xizang-South Tibet). ‘Modernity’ signifies development and economic progress critical to the survival of the Communist regime. Presently, China’s main security concerns are internal and Communist leadership is very sensitive regarding developments in Tibet, Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

Xi realises that hostile India does not augur well for China’s peaceful rise. To avoid India pivoting towards US-Japan axis, Beijing may be willing to yield tactical space to Delhi in view of its larger strategic interests. His ‘100 year’ plan seeks to manage contentious issues till China achieves great power status by mid of the century. Xi’s approach is in sync with Deng Xiao’s philosophy, “what can’t be resolved should be left to the next generation”.

Therefore, any significant progress on the border dispute is unlikely even in the distant future, more so given the prevailing asymmetry in the power differential due to China’s rapid rise. Moreover, its resolution is not in China’s interest as it will entail trade off and also erode Beijing’s ability to exert pressure on Delhi by escalating tension astride the Line of Actual Control (LAC) at will. Nonetheless, better border management mechanism and robust defence diplomacy will ensure tranquility along the LAC.

To address the issue of India’s prevailing trade deficit, President Xi proposed ministerial level economic and trade dialogue mechanism for joint manufacturing, besides alignment of economic strategies. As China’s industry is in the wake of transition to high-tech spectrum by 2025, shift of low-tech manufacturing to India will be in China’s interest.

China’s strategic culture lays great emphasis on ‘configuration of power’.9 In Chinese statecraft, nations are either hostile or subordinate. While allies are to be protected at all cost (case in point-Pakistan and North Korea), hostile nations ought to be taught befitting lesson and marginalised. China will continue to deepen its engagement with nations of South Asia to keep India neutralised. BRI is Xi’s grand initiative to further China’s strategic interests through geo-economics route. It aims to extend China’s outreach and gain multiple accesses to Indian Ocean. After all, Beijing cannot stake claim to be a superpower if it remains politically isolated and confined to Western Pacific.

From the Indian perspective, PM Modi has made earnest efforts, since coming to power in 2014, to project India as regional power and vie for greater role in the global affairs. His grand design to make India an important stake holder in Indo-Pacific and engage China on equal terms defies Xi’s strategic computation. While strengthening strategic partnership with USA, India has ensured continued engagement with China. Delhi needs to undertake a strategic review of its long term objectives, factoring both global and regional imperatives. Pragmatic China policy is needed to ensure strategic equilibrium in the region. This can be achieved only if India is able to achieve rapid pace of economic growth and scale up ‘Comprehensive National Power (CNP)’ to narrow down the existing gap vis-à-vis China.

As per former PM of Australia Kevin Rudd, President Xi is a man of extra ordinary intellect with a well-defined world view.10 He has a clear vision of establishing China centric global order by employing both hard and soft power. Beijing considers South Asia and Indian Ocean as region of immense strategic significance. China has developed close economic and military relations with most of India’s neighbours. Beijing seeks to neutralise Delhi politically and diplomatically so that it can pursue its national interests, disregarding India’s concerns. Immediately after Mamallapuram Summit, President Xi paid a day long visit to Nepal to upgrade Beijing-Kathmandu ties by pledging to boost economic cooperation and enhancing connectivity. Feasibility study of trans-Himalayan railway line project linking Xigaze to Kathmandu is expected to commence soon.11

India and China are in different camps, given their divergent visions and conflicting national interests. From series of stand offs over last couple of years including Doklam, Depsang and Demchok, Xi would have realised that Mao’s rationale of using force to negotiate with India has out lived its validity. Instead ‘soft sell’ approach by way of informal summits may offer better option. The real challenge for both sides is to keep the major contentious issues at bay and enlarge the scope of cooperation in the areas of convergence through sustained engagement. While reimagining ‘new era of cooperation’, India must be forth right in expressing its concerns and not hesitate from taking a tough call in pursuit of its national objectives as Chinese are ‘hard-nosed’ practitioners of realpolitik.

Endnotes

1 Indian Express (14 November 2019), Modi-Xi Meet at BRICS, Third Informal Summit in China Next Year, New Delhi. https://m.economictimes.com accessed on 24 November 2019.

2 China Daily Supplement-Hindustan Times (03 November 2017).

3 Henry Kissinger, (2011), On China, Allen Lane, Penguin Books, New York, p20.

4 Ackerman-Schroeder-Hwa Lo (2008), Encyclopaedia of World History, Bukupedia, p392-94. https://books.google.co.in accessed on 20 November 2019.

5 The Tribune, (13 October 2019), Xi’s Six Point Formula to Make Dragon and Elephant Dance Together, Chandigarh.

6 ibid

7 Chris Buckley and Steven Myers (11 March 2018), China’s Legislatures Bless Xi’s Indefinite Rule, New York Times.

8 White Paper ‘China’s National Defence in New Era, (July 2019), Foreign Language Press Beijing. www.xinhuanet.com accessed 20 November 2019.

9 Thomas G Mahnken (2011), Secrecy and Stratagem: Understanding Chinese Strategic Culture, The Lowy Institute of International Policy, Australia, p 18.

10 Kevin Rudd, (20 March 2018), What West Doesn’t Get About Xi Jinping, New York Times.

11 Wendy Wu (13 October 2019), Xi Jinping Promises to step up Chinese Support for Nepal as two-day visit Concludes, South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com accessed on 21 November 2019.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CXLIX, No. 618, October-December 2019

Baghdadi’s Elimination: ISIS Down but Not Out

The elimination of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the brutal founder of ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’ (ISIS), on October 27 is a significant achievement for the American counter-terrorism campaign. President Donald Trump while announcing Baghdadi’s death in a raid by the US Special Forces in northwest Syria said, “America and the world are safer today with leader of ISIS dead”.1

Baghdadi carried a bounty of US$ 25 million announced by the American Government, making him the world’s most wanted terrorist. Born as Ibrahim Ali al-Badri in Samarra, Iraq into a Sunni family in 1971, Baghdadi pursued his doctorate in Islamic studies at the Saddam University in Baghdad. Initially, he was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. In 2004, Baghdadi was arrested by the US troops in Fallujah and kept at Camp Bucca in Iraq for 10 months. It was here that he established a network of Islamist radicals.

The parent group of ISIS – the al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) – was founded in 2004 by a Jordanian Islamist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi by exploiting Sunni sentiments against Shiites. After Zarqawi and his two successors Abu Ayub al-Misri and Omar al-Baghdadi were killed in American attacks, Baghdadi took over the reins of a weakened AQI. However, shortly after the US withdrawal from Iraq towards the end of 2011, AQI under Baghdadi captured large tracts of territory in Iraq as well as Syria. Baghdadi later renamed AQI as the ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’.

In 2014, after declaring himself Caliph, Baghdadi ran a global terrorist network in over a dozen countries. His motive behind establishing a caliphate differed in concept from al Qaeda, under whom Baghdadi and his men had earlier operated. While Osama Bin Laden harboured designs to create a caliphate, he was sceptical of a strong response from the West which eventually turned out to be the reason why Baghdadi lost his State.2

Baghdadi exhorted terrorists to follow him, invoking religious fervour and hatred for non-believers, and skilfully employed the internet and media to urge his supporters to wage global jihad. He succeeded in establishing a ‘caliphate’ which lasted three years (2014-17) and included half of Syria and one-third of Iraq. At its peak, ISIS was the size of Britain with a population of around 12 million; a new normal for a ‘non state actor’ to challenge the very concept of ‘nation state’.

Baghdadi managed to evade capture for almost a decade by adopting stringent security measures as he did not trust even his closest associates. However, hunt for the ISIS chief had been on for some time. Detailed planning and preparations for the raid commenced a few months back when the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) got specific inputs on Baghdadi’s whereabouts in a village deep inside northwestern Syria, where he had sought shelter in the home of Abu Salama, a commander of another extremist group called Hurras al-Din. The Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) provided the vital real-time intelligence about Baghdadi’s movements to the US intelligence agencies.

The US Special Forces were in the process of closing on to Baghdadi when President Trump ordered the withdrawal of US troops from Syria in early October which disrupted the meticulous planning that was underway. This is said to have forced the Pentagon officials to hasten up the operation and go in for the risky night raid before the US troops and critical assets were pulled out.3

The raid per se was a difficult operation as the target was well inside the hostile territory dominated by the al Qaeda with airspace controlled by Syria and Russia. Incidentally, the mission had been called off twice earlier. As Baghdadi was expected to move out from his location any time, the raid had to be executed swiftly. The operation was cleared by Trump barely a few days before.

The operation was reportedly named after ‘Kayla Mueller’, an American aid worker who was abducted, raped repeatedly and killed by Baghdadi.4 For inserting the raiding force, eight CH-47 Chinook helicopters were employed. The heliborne force took off from a military base near Erbil in Iraq. Flying low to avoid detection, it took 70 minutes for the helicopters to reach Barisha, north of Idlib city in Syria. The ‘Delta Force’ comprising of Special Forces after being dropped in the vicinity of the target under covering fire went in for the walled compound, Baghdadi’s hideout. Trapped in a dead-end tunnel with no way to escape, Baghdadi blew himself along with two of his children by setting off the explosive vest he was wearing. Nine people were killed in the raid including senior ISIS leader Abu Yamaan.

The operation, executed with clockwork precision, was over in about two hours. The Delta Force accomplished its mission and exfiltrated virtually unscathed. This raid had many similarities with ‘Operation Neptune Spear’ which took out Osama Bin Laden hiding deep inside Pakistan on May 02, 2011. Both were heliborne operations undertaken by the US Special Forces based on hard actionable intelligence, deep inside hostile territory against top leaders of the world’s deadliest terrorist organisations.

Terrorist organisations are generally structured around a single leader who happens to be the core. Therefore, loss of top leadership has a devastating impact on such outfits, putting their very survival at stake. The killing of the ISIS chief followed by the elimination of his likely successor Abu Hassan al-Muhajir a day later in an American airstrike will weaken the ISIS global structures. On the other hand, it is a major boost to the US fight against terrorism as also a relief for anti-terror operations in other parts of the world.

The ISIS has tried to make inroads even into India by claiming to establish ‘Wilayah of Hind’ (India Province). It has called for jihad by raising sentiments around Kashmir. Around 100 Indians are believed to have joined ISIS in Syria. The ISIS will continue to make concerted efforts to recruit cadres from India and its neighbourhood. It can also collude with other terrorist organisations to carry out violent actions in India and pose a threat to overseas assets as well.

The ISIS may be down but not out as it is in the process of regrouping. A large number of ISIS cadres estimated to be over 25,000 are known to have survived. While confirming the demise of Baghdadi in the US raid, ISIS has vowed to avenge its chief’s death. It has already appointed Abu Ibrahim al-Hashmi as the new chief.5 The outfit has also changed its tactics by avoiding major terrorist actions. Instead, it has been mounting small scale operations through its sleeper cells across Syria and Iraq; besides ‘lone wolf’ strikes, making detection and prevention by law enforcement agencies extremely difficult. The decentralised ‘wilayahs’ are quite active in various parts of the world, especially in West Africa and South Asia.

Given the superpower rivalry and ensuing hostility amongst the regional players, West Asia (or the Middle East) is likely to remain in a state of flux. The departure of the American troops from Syria will have serious consequences both for the US and its allies in the region. While it would help Iran as well as ISIS, the interests of Israel and Saudi Arabia will definitely be hurt. Given the scenario, any relaxation of pressure will give ISIS room for manoeuvre and ability to garner support of local allies. This could prove catastrophic if timely countermeasures are not taken by the global polity to strike at the ISIS roots.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1.Rukmini Callimachi and Falih Hassan, “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, ISIS Leader Known for His Brutality, Is Dead at 48,” The New York Times, October 27, 2019 (Accessed October 30, 2019).

- 2.Ibid.

- 3.Eric Schmitt, Helene Cooper and Julian E. Barnes, “Trump’s Syria Troop Withdrawal Complicated Plans for al-Baghdadi Raid,” The New York Times, October 27, 2019 (Accessed October 30, 2019)

- 4.Dan Lamothe and Ellen Nakashima, “With Baghdadi in their sights, U.S. troops launched a ‘dangerous and daring nighttime raid’,” The Washington Post, October 28, 2019 (Accessed October 31, 2019)

- 5.Hesham Abdulkhalek and Ulf Laessing, “Islamic State vows revenge against U.S. for Baghdadi killing,” Reuters, October 31, 2019 (Accessed November 01, 2019)

Hong Kong unrest tests China’s mettle

Published in IDSA on Aug 27, 2019

Maj Gen GG Dwivedi (retd)

Former Defence Attaché in China

Hong Kong’s basic character has changed under China’s control. The chief executives of the territory have gradually become more responsive to the efforts of the mainland leadership to dilute the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ arrangement by impinging on civil liberties. China has been blamed for whisking people onto mainland for detention and torture.

Hong Kong’s return to the motherland on July 1, 1997, marked the reversal of the ‘Century of Humiliation’ (1839-1949), a period during which China suffered a series of ignominious defeats at the hands of colonial powers. Forced to yield to the will of the victors, leasing of Hong Kong Island to Britain in 1898 for 99 years was one such act of concession.

Since the handover, July 1 has been observed as a public holiday (Establishment Day) in Hong Kong. This year, instead of celebrations, it turned out to be a day of rebuking the Chinese rule, as anti-government protesters stormed into and ransacked the city’s Legislative Council, displaying British-era colonial flags. Territory’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s claims of ‘22-year successful Chinese rule’ sounded hollow as the protests laid bare the reality of the deeply fractured Hong Kong society. Around a million of Hong Kong’s 7 million population took to the streets.

Violent protests against the city administration began in mid-June this year, arising from the fear of eroding freedom. The trigger was the Hong Kong’s Government’s move to pass the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Bill (Extradition Bill) which would allow Hong Kong citizens and foreigners accused of crimes to be extradited for trial to mainland China. This was seen as a deliberate attempt by the government to undermine the independence of Hong Kong’s legal system. Two days after the protests, Lam said the government won’t proceed with the law until public anxieties and fears were properly addressed.

Not convinced, a week later, thousands of protesters marched on streets of Tsim Sha Tsui, a popular tourist area of Hong Kong, in a bid to gain support from the mainland Chinese visitors. On July 9, Lam finally admitted that her administration’s attempt to introduce the Extradition Bill was a failure and assured that the government would not seek to revive it in Parliament. However, she refused to give in to the demand to withdraw the Bill from the legislative agenda, which led to a provocative response from the anti-government camp.

The daily rallies have been marked by increasing violence and confrontation with the police. The protesters have also demanded direct election to the city’s Chief Executive, currently chosen by Beijing. Hong Kong citizens’ real resistance is against People’s Republic of China. Li Bijian, Minister at Chinese Embassy in India has said, “What happens in Hong Kong is China’s internal affair. China will safeguard its sovereignty, security and development interests, and Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability.”

Hong Kong, which had been under British rule for a century and a half, had acquired the status of a major global financial centre. Therefore, at the time of handover, in order to maintain Hong Kong’s prosperity, its legal system and culture, the Chinese Communist leadership agreed to a unique arrangement, ‘One Country, Two Systems’, enshrined by Deng Xiaoping. It implied that Hong Kong will legally be part of China, but as a ‘Special Administrative Region’ with freedom to enact its own laws (excluding foreign policy and defence) and enjoy freedom of speech and independent judiciary for the next 50 years.

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) arrangement was not without scepticism, vindicated by several protest movements since the handover. In 2003, the HKSAR Government Chief Executive made a bid to introduce legislation redefining the scope of ‘treason’ that would have drastically curtailed freedom to criticise the Chinese Government. In 2014, there were large scale pro-democracy protests demanding an end to China’s surreptitious encroachment on citizens’ liberties. These went on for months and came to be known as the ‘Umbrella Movement’. The movement fizzled out due to the government’s unrelenting stance against making concessions to the protesters.

Hong Kong’s basic character has changed over the past two decades under China’s control. The territory’s chief executives over the years have become more responsive to the efforts of the mainland leadership to dilute the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ arrangement by gradually impinging on civil liberties. China has been blamed for whisking people out of Hong Kong onto the mainland for detention and torture. Even the local media is restrained today while reporting on issues considered sensitive by the Communist leadership.

In economic terms, Hong Kong’s clout has diminished over the years. In 1997, its GDP was almost one-fifth of China’s, while now it is down to 3 per cent. With significant presence of Chinese companies and financial institutions in Hong Kong, HKSAR dependence on the mainland has increased. Shanghai, given its rapid growth as China’s financial capital, could emerge as a viable alternative to Hong Kong.

Political developments on the mainland don’t augur well for Hong Kong. Since President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2013 as the Fifth-Generation Leader, the Communist Party rule has become more authoritarian and assertive, both at home and abroad. Yang Jiechi, politburo member, Communist Party of China, has blamed the US and other Western countries for stirring trouble, whereas the movement appears to be indigenous.

Today, China’s security concerns are primarily internal as it faces virtually no external threat. Hence, sovereignty and stability stand out as its key national objectives, implying ‘zero tolerance’ to any kind of dissent. As per its latest white paper, National Defence in New Era, China retains the option to use force to unify Taiwan. Regarding Hong Kong’s situation, Beijing wants the city administration to halt the protests and deal with pro-democracy activists sternly. The protesters may have forced Lam to yield ground on the Extradition Bill, but in the long run, Beijing expects the movement to peter out as it tightens control over HKSAR. However, young activists like Joshua Wong, a Nobel Peace Prize nominee who was convicted and jailed in 2017 and released recently, are proving a tough nut to crack.

Massive drills involving some 12,000 soldiers of the Chinese People’s Armed Police (PAP) — part of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) — along with armoured vehicles were staged at Shenzhen, a city in southern China adjacent to Hong Kong on August 6. It was meant to convey a veiled threat to the protesters of possible intervention. The PLA garrison in Hong Kong so far has remained confined to the barracks. Should the situation take a turn for the worse, the Communist leadership has the will to quell the protests by force, catastrophic consequences notwithstanding. However, Global Times, a government-controlled English daily, in a rare reference to Tiananmen, has insisted that the country has more sophisticated methods to handle the Hong Kong crisis than those employed 30 years ago.

The current impasse in Hong Kong poses the most serious challenge to the Chinese leadership since the territory’s integration with the mainland. The ‘One Country, Two Systems’ arrangement is at the crossroads, set to be consigned to the archives well before 2047— its expiry year.

Xi’s Belt-Road Initiative: Recalibration, Strategic Imperatives

The second Belt-Road Forum (BRF) was held in Beijing from 25-27 April 2019. The three-day event was organized to promote the ‘Belt-Road Initiative’ (BRI) – President Xi Jinping’s multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure development and investment venture. The Summit was attended by 40 global leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin and Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan, China’s two closest allies. The gathering was larger than the first Summit held in 2017, which had just 29 participants. Among the new entrants were Austria, Portugal, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore and Thailand. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte became the first G7 leader to join the BRI. India stayed out for the second time on grounds of sovereignty given that the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) traverses through Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK).

BRI has come under fire due to lack of transparency, weak institutional mechanism, scepticism about Chinese loans leading to debt trap, and poor environmental record. Besides, it is being perceived as an exclusive ‘Chinese Club’. With new deals aggregating US$ 64 billion signed and 283 concrete deliverable outcomes, despite criticism particularly from the US and its allies, the grand plan apparently remains on track and is gaining international traction. With a view to dispel growing concerns, the focus of this second Forum was on projecting BRI as an attractive investment destination. President Xi staunchly defended the Belt-Road, assuring its ‘win-win’ outcome.

BRI provides China a unique platform to pursue its multiple objectives. Besides expanding global influence, it is in sync with President Xi’s ‘China Dream’ (Zhong Quo Meng), envisioning a ‘powerful and prosperous’ China. Numerous hurdles notwithstanding, the Belt-Road Initiative is bound to impact the prevailing geopolitical dynamics and have strategic ramifications. It merits a pragmatic evaluation.

BRI: An Appraisal

The mammoth infrastructure development initiative was originally conceptualized as a ‘going out’ strategy to develop productive outlets for China’s domestic overcapacity, diversify foreign asset holdings, and contribute to the stabilization of the Western provinces and the Eurasian hinterland. It was in 2013 that President Xi Jinping launched the ‘One Belt-One Road’ (OBOR) project, later rechristened as BRI. The initiative was portrayed as a benign investment venture – a ‘road of peace and prosperity’ with vast benefits. Spanning across Asia, Africa, Oceania and South America, the total value of the scheme was estimated at $ 3.67 trillion. According to the World Bank, the plan is expected to lift global GDP growth by three per cent.

China’s initiative evinced interest from a large number of countries since it was filling the void left by International Financial Institutions (IFI) which had stopped financing infrastructure development. BRI is in no way a traditional aid programme, but a money-making investment. It blends political, economic and strategic dimensions. Being country specific, the approach adopted varies from resolving debts, accepting payments in cash, commodities or in lease. Investments in many cases seek to further core Chinese national interests including gaining access to sensitive ports and securing sea lanes of communication in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Alongside the physical infrastructure, another ambitious project on the anvil is the ‘digital silk road’ aimed at enhancing digital connectivity. This will enable Chinese dominance of 5G technology and networks, arousing concerns amongst Western nations.

A few BRI countries had expressed dissatisfaction with the on-going ventures including Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Several projects under CPEC also came under the scanner. A hydro-power project in Nepal was scrapped. The Trump administration holds the view that China’s ‘predatory financing’ pushes smaller countries into debt, endangering their sovereignty. Beijing’s acquisition of Hambantota port on 99-year lease in a debt swap agreement in 2017 is a case in point. Recently, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo slammed China while addressing the opening session of the ‘Arctic Council’ in Finland for using its power through BRI to achieve security objectives.

The exact number of projects under BRI is hard to calculate, though these run into thousands because many have been informally negotiated. Most striking of the Belt-Road ventures is the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) which will connect Malaysia’s East Coast to Southern Thailand and Kuala Lumpur. CPEC, connecting Xinjiang with Gwadar and the ‘Gulf of Oman’ is a signature project. Total trade between China and BRI nations has exceeded $ 6 trillion. Chinese investment in these countries stands at over $ 80 billion. BRI provides China an overarching framework for enhancing bilateral and multilateral cooperation.

Recalibration and Branding

In the wake of growing international criticism, President Xi recognised the need to review and recalibrate the BRI. During the April 2019 Summit, he vouched for China’s sincerity and vowed ‘zero tolerance’ on corruption while assuring deliverance of ‘high quality’ schemes in consonance with international standards. Key concerns, namely cleaning of state subsidies, reducing non-tariff barriers, boosting imports and protecting ‘Intellectual Property Rights’, were also highlighted.

China has been criticised for allowing its companies to take away 90 per cent of the business and dictating own financing terms to borrowers. Xi reaffirmed that BRI would adopt market-driven practices, making financial terms negotiable between lenders and borrowers. He also indicated that new rules will be formulated within the framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Signs of partial backtracking by China are evident from the fact that Malaysia has renegotiated the terms of the rail project with a much-reduced outlay and increased local participation. Even Pakistan is in the process of reviewing the terms of CPEC.

According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, with the policy refresh in implementing BRI, it will be less of a political target in future. In the image building exercise, Belt-Road has now been termed as a ‘community of common destiny’. A kind of G150, it seeks to promote multilateralism, globalisation and development, alongside human rights, providing an umbrella for plurilateral cooperation. BRI manifests China’s confidence as a global player, gradually stepping into the strategic space yielded by the USA.

India’s Stance on BRI

India once again chose to keep out of the BRF since the reasons for its abstention from the 2017 Summit remain valid. According to the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), connectivity initiatives must be based on universally recognised international norms, good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency and equality. It further stressed that projects should not create a debt burden and instead empower local communities.

At a pre-Summit conference, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasised that Sino-Indian ties were insulated from the differences over BRI. He said that China understood India’s concerns about CPEC. According to China’s Ambassador to India, Luo Zhaohui, better connectivity between the two countries could be the key to address the existing trade deficit and bring more strategic convergence on India’s ‘Act East Policy’.

India’s keeping out of the BRI does not count for much unless it has a blueprint to counter China’s grand design. New Delhi’s first regional initiative, its ‘Connect Central Asia Policy’ (CCAP), is a step in the right direction as it reflects the nation’s will to play a larger role in the region. The ‘Trilateral Agreement’ between Afghanistan, India and Iran offers an excellent opportunity to implement a ‘Look North Strategy’. There is vast scope for connectivity with ASEAN as well.

Strategic Imperatives

Despite impediments, China remains steadfast in pushing through the BRI to achieve its multiple objectives. The BRI now dominates Beijing’s geo-economic discourse. Growing apprehensions about the sustainability of various projects and the burgeoning debt burden of the recipient countries have led to serious doubts over the long-term viability of such a mega venture, putting China’s credibility at risk. Consequently, the focus of the recent Summit was on dispelling misgivings.

BRI is primarily South Asia and IOR centric, as is evident from the number of projects in these regions – CPEC, CMEC (China-Myanmar Economic Corridor), ‘Nepal-China Trans Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network’ including Nepal-China cross border railway, besides significant projects in Bangladesh, Maldives and Sri Lanka. The Maritime Silk Route encompasses major ports such as Kyakhphu in the Bay of Bengal and Gwadar in the Arabian Sea. On completion of the above ventures, China will enjoy a competitive edge in the region.

India has rightly chosen not to participate in the Forum as there is no viable opportunity for it. New Delhi needs to closely monitor the infrastructure development activities in the region from the strategic perspective and within the larger framework of relations with Beijing. At the same time, it must pursue alternate connectivity initiatives like the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) in collaboration with partners such as Japan to ensure geostrategic balance in the region.

China’s Communist leadership is known for grand initiatives. President Xi’s Belt-Road is one such mega venture. While still in the evolution stage, BRI has the potential to be a game changer in China’s quest to shape a ‘Sino-Centric’ Global Order.

Doctrinal Shift: Decoding China’s Way of War Fighting

Published in USI Journal Book

Abstract

Chinese leaders are known to have penchant for nations history. To decode China’s doctrine and its ways of war fighting, it is imperative to have a deeper understanding of its strategic culture. Hard power, an important component of Chinese concept of ‘Comprehension National Power’ (CNP) has been frequently employed by its leadership in pursuit of national interests. Beijing has continuously refined its war- fighting doctrines in consonance with prevailing security environment. Its current military doctrine of “Local War under Informationisation Conditions” is well aligned to further nation’s quest to acquire superpower status. China’s rapidly growing military capability under President Xi Jinping has serious implications for the global polity.

Genesis

The Chinese thinkers have a great sense of history, vindicated by an old proverb; “Farther you look back-further you look ahead”. Thought process of Chinese leadership continues to be influenced by ancient wisdom, deeply rooted in four and half millennium old civilization. Hence, to comprehend the essence of China’s doctrinal architecture and decode its ways of warfighting, it is imperative to gain insight into its history and strategic culture.

In the Confucian doctrine, Guanxi implies reciprocal relationship based on ‘network of balanced interactions’ amongst the states1. Yizhan on the other hand, pertains to ‘tenets of righteous warfare’- a concept which emerged during the turbulent ‘Spring-Autumn’ period (770-476 BCE). Whereas, Sun Zi ‘doctrine of legalism’ enunciated in the classic ‘Art of War’ set in the Warring Period’ (475-221 BCE) propounded military as an instrument to rein in the adversary. Traditionally, Chinese strategic thinking professed that best way to respond to threat was by eliminating it; stressing the value of violent solutions to conflict, with preference to offensive over defensive strategies. No surprise, China used force eight times during the period 1950-85.

During the ‘Imperial Era’, Chinese security strategy was centred on the defence of heartland, encompassing plains of Yellow River in the North and Yangze River in the South, against threat emanating from bordering regions namely Xinjiang, Mongolia (both Outer and Inner), erstwhile Manchuria and Tibet. The basic strategy was a mix of border defence and employment of coercive and non-coercive means2. China remained unified except for two brief periods (220-589 AD and 907-960 AD) when it was fragmented. Besides, there were two non-Han dynasties; (Yuan 1279-1368 and Qing 1644-1910). The Chinese strategists harbour a firm belief that their country was more secure when internally strong, with subdued neighbourhood, ensuring peaceful periphery.

Chinese emperors sought tribute from weaker nations, pursuing expansionist and hegemonic policies. It was due to the weakness of the Qing Dynasty and continental mind-set that China lost its prime position. The Chinese attribute their nation’s suffering during the ‘century of humiliation’; period from First Opium War (1839-42) to1949, primarily to twin factors i.e. internal unrest and foreign aggression (Nei Luan-Wai Huan).

China’s military strategic culture lays great emphasis on Shi i.e. strategic configuration of power to achieve specific objectives. Aim is not to seek annihilation but relative deployment of own resources to gain position of advantage or ‘strategic encirclement, as in the game wei qi3. China’s latest grand initiatives, namely the ‘Belt-Road’ and ‘Maritime Silk Route’ are adaptions of this strategy. Surprise and deception marked by unpredictability are the inherent component of Chinese stratagem. Every move is thought through on the checker board. Negotiation process is always long drawn-to force a favourable deal.

|

Even today, Chinese military handbooks routinely refer to old classics and battles fought some four thousand years back. A case in point is Dr Henry Kissinger’s narration about Chairman Mao briefing his commanders on the eve of ‘1962-Sino-Indian War’ in his seminal book ‘On China’. Mao recalled that China and India had fought one and half wars earlier. First one was during the Tang Dynasty when Wang Xuanxe led

Sino-Tibetan force against King Harshavardhana’s rebellious successor to

avenge humiliation in 649 AD. The ‘Half War’ was Timurlane ransacking Delhi, some 700 years later. The historic lesson, as Mao put it; “Post China’s interventions, the two countries enjoyed long period of peace and harmony. But to do so, China had to use force to ‘knock’ India back to negotiation table”4.

Chinese defence doctrines post 1949 have been based on the grand strategy, factoring national objectives and threat perceptions, drawing richly from the past. Its war fighting ways have continuously evolved, marked by

major doctrinal shift. In the earlier stages, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was constrained to fight with whatever weapons that were available. Over a period of time, with Chinese capability to produce high-tech systems, it is now the doctrine which drives the choice of weapons.

The paper delves into the dynamic process of China’s doctrinal shift, its capacity building and ways to prosecute the future wars.

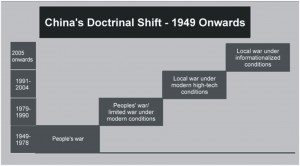

Doctrinal Shift-Since 1949

During the four decades period from 1911-49, China as a Republic made tectonic transition from Imperial Era to a Communist State – the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The architect of this shift was the Communist Party of China (CCP). Established in 1921, under Mao, its main stay was ‘peasant revolution’. The highlight of Communists eight years ‘civil war’ campaign culminating in successful revolution in 1949 was the national power; its key components being the political agenda, mass support and propaganda machine5.

China has long theoretical and historical tradition of seeking asymmetric responses to strategic challenges. The concept of asymmetric warfare originated with Sun Zu emphasizing numerous strategies to defeat the enemy, later Mao propagating the ‘people’s war’ concept of exploiting the masses.

Mao’s ‘People’s War’ doctrine was driven by the vital national interestsPeople’s War (1949-78)

i.e. unity, security and economic progress, premised on the defence of hinterland. It was configured around the notion of ‘total war’ which included employment of nuclear weapons by the adversary. Defensive in nature, it was to be fought by luring enemy deep into Chinese territory, causing attrition in a gradual manner, trading space for time, characterised by mass employment of regular troops to make up for inferior weapon systems, with heavy reliance on militia forces.

|

Mao’s strategy was a combination of ‘Protraction and Attrition’; implied

diplomatic manoeuvre with the strong and coercion against weak. In 1949, PRC aligned with erstwhile Soviet Union to ward off threat from Japan. In October 1950, PLA marched into Tibet, re-establishing Chinese control to ensure stable periphery. Around the same time, perceiving Mac Arthur’s advance across the 38th Parallel as threat to the mainland, China jumped into the Korean War. In pursuit of the ‘People’s War’ Doctrine, Mao went in for limited war against ill prepared India in 1962, to keep the neighbour restrained. Again in 1969, with border tension leading to Ussuri River skirmish (Damanski-Zhenbao Islands), Mao took on President Brezhnev. By openly challenging Soviet Union, China was able to set stage for reconciliation with America to imbalance the adversary.

People’s War/Local War under Modern Conditions (1979-90)

In February 1979, China launched a massive attack on Vietnam to reassert its control over the latter, in pursuit of its ‘peaceful periphery’ policy. It was in keeping with its aggressive strategy of using force to achieve political objectives. PLA performed poorly which led to review of its doctrine and structures This also coincided with Deng Xiaoping’s ‘four modernisations’ drive launched in December 1978. The new military doctrine-“People’s War under Modern Conditions” was focused on mitigation of threat from the Soviet Union. Earlier concept centred on defence was revised in favour of mobile warfare, with pre-eminence of modern weapons in war fighting. Towards the mid-1980s, with the gradual decline of Soviet Union and change of threat perception, there was again a strategic review, resulting in the formulation of new doctrine of “Local War under Modern Conditions”.

Local War under High Tech Conditions (1991-2004)

The high intensity ‘1991 Gulf War’ and changed international situation were key factors for PLA to initiate major doctrinal reforms during the 1990s. In 1995, the Central Military Commission (CMC) the highest military body put forth ‘New Generation Operation Regulations’ (xin yidai zhuozhan tiaoling) to ‘fight and win future wars’. The two transformations (liangge zhuanbian) sought to make Chinese military undergo metamorphoses; first-from an Army preparing to fight and win ‘local wars under ordinary conditions’ to fight and win ‘local wars under high-tech conditions’ and second-to transform the armed forces from one based on quality to one based on quality. An important component of the new doctrine was the concept of ‘War Zone Campaign’ (WZC)”. More offensive in design; ‘active defence’ being the core element, it encompassed controlled space and time, deployment of Rapid Reaction Forces (RRFs) and combined arms operations.6 It envisioned prosecution of future campaigns under ‘Unified Joint Services Command’ guided by the CMC.

|

China’s White Papers act as authentic indicators of doctrinal shift since the late 1990s. The first ‘White Paper’ was released in July 1998 titled “China’s National Defence7”. It was for the first time that PRC systematically expounded on its defence policies and explicitly expressed its new outlook on security. Second ‘White Paper’ followed two years later which laid stress on China’s priorities in safeguarding sovereignty and territorial integrity. Another ‘White Paper’ on ‘China’s National Defence’

was released in December 2002 which brought China’s core national interests as the fundamental basis for formulation of the defence policy. The ‘Gulf War 2003’ demonstrated the importance of ‘mechanisation’ and ‘informationisation’. In 2004, President Hu Jintao laid down revised mandate for the military; “to win local wars under informationised conditions”.Consequently, the 2004 ‘White Paper’ propounded the idea of dual historic mission of ‘mechanisation and informationisation’, besides delving on the concept of ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA) with Chinese characteristics8.

Local War under Informationised Conditions (2005 onwards)

The first decade of the new millennium was perceived by the Chinese strategic community as the ‘critical period of multi-polarisation’ leading to the review of national security strategy, dealt in the ‘White Paper’ released in 2006. As per threat assessment by the security experts, probability of full-scale external aggression was unlikely in the near terms. However, in the

future conflicts, the PLA would be faced with technologically superior adversary. Therefore, the idea behind reframing national doctrine from ‘high-tech conditions’ to ‘informationised conditions’ was on the assumption that through informationised conditions, technologically superior adversary could be defeated.

Chinese military doctrine of ‘Local Wars under Informationised Conditions’ has two components. ‘Local Wars’ envision short swift engagements with limited military objectives in pursuit of larger political aim. ‘Informationised Conditions’ refers to the penetration of technology into all walks of modern life, but specific to war fighting includes IT, digital and ‘artificial intelligence’ applications. It implies network-centric environment and waging information operations to ensure battlefield domination. In essence, the aim is to achieve complete security of PLA networks while totally paralyzing that of adversary’s. This encompasses electronic warfare along with psychological warfare and deception to attack enemy’s Command, Control, Communications, Computer, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems, employing both hard and soft kills.

The concept of ‘informationisation’ is broad-based, all-inclusive and gives prominence to information ascendency as the decisive determinant and the key battle-winning factor. Salient operational facets of ‘Limited War under Modern

Informationised Conditions’ include induction of high-tech force multipliers, network centricity, Information Warfare (IW), jointness and interoperability, control of outer space, integrated forward logistics system and ideal man-machine mix.

Decoding – China’s Ways of War Fighting

As evident from the above, the Communist leadership has continuously reviewed the war fighting doctrines in consonance with prevailing security environment. To visualise the future course, it is important to analyse the rationale behind path- breaking military reforms initiated by President Xi Jinping over the last five years. On assuming the mantle of the Fifth Generation leadership in 2012, President Xi unfolded ‘China Dream’ (fixing-restoration) which envisions ‘powerful and prosperous’ China. To translate his ‘China Dream’ into reality, he outlined twin objectives; first to become ‘fully modern economy by 2035’ and acquire ‘great power status by 2049’. President Xi Jinping foresees China to be the key player in shaping the new world order with Chinese characteristics. Alongside stability and economic progress, sovereignty is a glue to foster nationalism. It implies security of periphery and integration of Taiwan and other claimed territories with the motherland, wherein use of force remains an option.

|

The sense of urgency with which President Xi Jinping initiated the transformational process could be attributed to the geopolitical considerations – U.S. strategy of rebalancing to Asia-

Pacific being a major factor. The underlying rationale behind the critical reforms was twofold; firstly prepare the military for China’s expanding global role and secondly, establish Party’s firm control over the PLA through the revamped CMC. The Ninth ‘White Paper’ on ‘National Defence’ published in May 2015 was titled ‘China’s Military Strategy’. Its focus is on building strong national defence and powerful armed forces as a security guarantee for China’s peaceful development. The theme is ‘active defence’ and stress remains on winning ‘local wars under conditions of modern technology’9. Priority has been accorded to Navy and Air Force vis-à-vis the ground forces. It also marked a shift in the naval strategy from ‘off shore waters defence’ to combined strategy of ‘off shore waters defence and open sea protection’ to secure its maritime interests. Establishment of ‘Air Defence Identification Zone’ (AIDZ) is in sync with the new strategy.

Salient facets of China’s future was fighting are as under10:-

- Adopt holistic approach to balance ‘war preparation’ and ‘war prevention’, create favourable posture, resolutely deter and ‘win informationised local wars’.

- Respond to multi-directional security threats; adhere to principles

of flexibility and mobility to facilitate concentration of superior forces while ensuring self- dependence.

- Employ integrated combat forces to prevail in system-vs-system operations, featuring information dominance, precision strikes and joint

- Plan for strategic deployment and military dispositions to clearly divide areas of responsibility, with the ability to support each other as organic whole e. reorientate from ‘theatre’ to ‘trans-theatre’ operations.

- Build a modern system of military forces with Chinese characteristics and constantly enhance

- Continue to pursue the strategy of “Nibbling and Negotiating” (yi bian dan, yi bian da -talking and fighting concurrently); case in point, its actions in the South China Sea.

- As part of defence diplomacy, expand military cooperation with major powers and neighbouring countries, for the establishment of regional security framework.

To align the specific services potential with the above strategic direction, salient advances in the armaments are designed to achieve domination in the field of information warfare, anti-radiation missiles, electronic attack drones, direct energy weapons, airborne early warning control system, anti-satellite weapons and cyber army under the ‘Strategic Support Force’11. Even the focus of the Chinese military publications dealing with new modes of war fighting is on jointness and space-based operations. Information based operations are an on-going process, conducted even during the peace time, which could prove a valuable asset during the times of conflict.

|

Key Result Areas (KRAs) for the services have been clearly defined in keeping with the higher strategic direction. PLA Army (PLAA) is required to reorient from ‘theatre defence’ and adapt to precise ‘trans-theatre mobility’ missions. PLA Navy (PLAN) while gradually shifting focus to ‘offshore waters defence with open sea protection’ is required to build a combined, multi-functional and efficient maritime force structures. PLA Air Force (PLAFF) in line with the strategic requirements to execute informationised operations is to create requisite structures to ensure transition from erstwhile territorial air defence to building air-space capabilities. Besides it is also expected to boost early warning, air strike, information counter measures and force projection potential.

The ‘Rocket Force’ is adopting transformational measures through reliance on technology upgrades; enhance safety and reliability of missile systems both nuclear and conventional, thus strengthening strategic deterrence. The ‘Strategic Support Force’ is to deal with challenges in the outer space and secure the national space assets. Besides, it is also required to expedite the development of ‘Cyber Force’ by enhancing situational awareness and security of national information networks.

Systems and structures have been revamped across the board. At the macro level, major changes have been instituted with focus on civil- military integration, jointness and speedy decision-making process. With the

redefined role, CMC is now responsible for formulating policies, controlling all the military assets and higher direction of war. As a sequel to the military reforms, the Theatre Commanders directly report to the CMC.

At the operational level, erstwhile 17 odd Army, Air Force and Naval commands have been reorganised into five ‘Theatre Commands’ (TCs); Eastern, Western, Central, Northern and Southern. With all the war fighting resources in each battle zone placed under one commander ensures seamless synergy in deploying land, air, naval and strategic assets in a given theatre. In addition, 84 corps level organisations have been created including 13 operational corps, as well as training and logistics installations. Given the sensitivity of Korean Peninsula and disputed islands territories, the deployment is biased towards Eastern and Northern Theatres. The broad area of responsibility of the reorganised TCs is as under:-

| | Eastern–Nanjing | (Taiwan, East China Sea) | – 71, 72 & 73 Corps |

| | Southern–Guangzhou | (Vietnam and South China Sea) | – 74 &75 Corps |

| | Western–Chengdu | (India & Internal Security) | – 76 &77 Corps |

| | Northern–Shenyang | (Korean Peninsula & Russia) | – 78, 79 & 80 Corps |

| | Central–Beijing | (Internal Security & Reserves) | – 81, 82 & 83 Corps |