Published in USI Journal Book

Abstract

Chinese leaders are known to have penchant for nations history. To decode China’s doctrine and its ways of war fighting, it is imperative to have a deeper understanding of its strategic culture. Hard power, an important component of Chinese concept of ‘Comprehension National Power’ (CNP) has been frequently employed by its leadership in pursuit of national interests. Beijing has continuously refined its war- fighting doctrines in consonance with prevailing security environment. Its current military doctrine of “Local War under Informationisation Conditions” is well aligned to further nation’s quest to acquire superpower status. China’s rapidly growing military capability under President Xi Jinping has serious implications for the global polity.

Genesis

The Chinese thinkers have a great sense of history, vindicated by an old proverb; “Farther you look back-further you look ahead”. Thought process of Chinese leadership continues to be influenced by ancient wisdom, deeply rooted in four and half millennium old civilization. Hence, to comprehend the essence of China’s doctrinal architecture and decode its ways of warfighting, it is imperative to gain insight into its history and strategic culture.

In the Confucian doctrine, Guanxi implies reciprocal relationship based on ‘network of balanced interactions’ amongst the states1. Yizhan on the other hand, pertains to ‘tenets of righteous warfare’- a concept which emerged during the turbulent ‘Spring-Autumn’ period (770-476 BCE). Whereas, Sun Zi ‘doctrine of legalism’ enunciated in the classic ‘Art of War’ set in the Warring Period’ (475-221 BCE) propounded military as an instrument to rein in the adversary. Traditionally, Chinese strategic thinking professed that best way to respond to threat was by eliminating it; stressing the value of violent solutions to conflict, with preference to offensive over defensive strategies. No surprise, China used force eight times during the period 1950-85.

During the ‘Imperial Era’, Chinese security strategy was centred on the defence of heartland, encompassing plains of Yellow River in the North and Yangze River in the South, against threat emanating from bordering regions namely Xinjiang, Mongolia (both Outer and Inner), erstwhile Manchuria and Tibet. The basic strategy was a mix of border defence and employment of coercive and non-coercive means2. China remained unified except for two brief periods (220-589 AD and 907-960 AD) when it was fragmented. Besides, there were two non-Han dynasties; (Yuan 1279-1368 and Qing 1644-1910). The Chinese strategists harbour a firm belief that their country was more secure when internally strong, with subdued neighbourhood, ensuring peaceful periphery.

Chinese emperors sought tribute from weaker nations, pursuing expansionist and hegemonic policies. It was due to the weakness of the Qing Dynasty and continental mind-set that China lost its prime position. The Chinese attribute their nation’s suffering during the ‘century of humiliation’; period from First Opium War (1839-42) to1949, primarily to twin factors i.e. internal unrest and foreign aggression (Nei Luan-Wai Huan).

China’s military strategic culture lays great emphasis on Shi i.e. strategic configuration of power to achieve specific objectives. Aim is not to seek annihilation but relative deployment of own resources to gain position of advantage or ‘strategic encirclement, as in the game wei qi3. China’s latest grand initiatives, namely the ‘Belt-Road’ and ‘Maritime Silk Route’ are adaptions of this strategy. Surprise and deception marked by unpredictability are the inherent component of Chinese stratagem. Every move is thought through on the checker board. Negotiation process is always long drawn-to force a favourable deal.

| China’s military strategic culture lays great emphasis on Shi i.e. strategic configuration of power to achieve specific objectives. Aim is not to seek annihilation but relative deployment of own resources to gain position of advantage or ‘strategic encirclement, as in the game wei qi. |

|

Even today, Chinese military handbooks routinely refer to old classics and battles fought some four thousand years back. A case in point is Dr Henry Kissinger’s narration about Chairman Mao briefing his commanders on the eve of ‘1962-Sino-Indian War’ in his seminal book ‘On China’. Mao recalled that China and India had fought one and half wars earlier. First one was during the Tang Dynasty when Wang Xuanxe led

Sino-Tibetan force against King Harshavardhana’s rebellious successor to

avenge humiliation in 649 AD. The ‘Half War’ was Timurlane ransacking Delhi, some 700 years later. The historic lesson, as Mao put it; “Post China’s interventions, the two countries enjoyed long period of peace and harmony. But to do so, China had to use force to ‘knock’ India back to negotiation table”4.

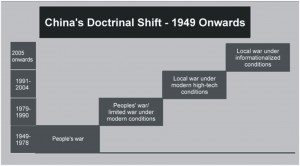

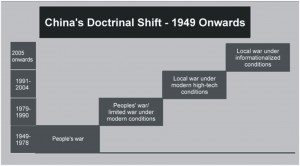

Chinese defence doctrines post 1949 have been based on the grand strategy, factoring national objectives and threat perceptions, drawing richly from the past. Its war fighting ways have continuously evolved, marked by

major doctrinal shift. In the earlier stages, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was constrained to fight with whatever weapons that were available. Over a period of time, with Chinese capability to produce high-tech systems, it is now the doctrine which drives the choice of weapons.

The paper delves into the dynamic process of China’s doctrinal shift, its capacity building and ways to prosecute the future wars.

Doctrinal Shift-Since 1949

During the four decades period from 1911-49, China as a Republic made tectonic transition from Imperial Era to a Communist State – the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The architect of this shift was the Communist Party of China (CCP). Established in 1921, under Mao, its main stay was ‘peasant revolution’. The highlight of Communists eight years ‘civil war’ campaign culminating in successful revolution in 1949 was the national power; its key components being the political agenda, mass support and propaganda machine5.

China has long theoretical and historical tradition of seeking asymmetric responses to strategic challenges. The concept of asymmetric warfare originated with Sun Zu emphasizing numerous strategies to defeat the enemy, later Mao propagating the ‘people’s war’ concept of exploiting the masses.

Mao’s ‘People’s War’ doctrine was driven by the vital national interestsPeople’s War (1949-78)

i.e. unity, security and economic progress, premised on the defence of hinterland. It was configured around the notion of ‘total war’ which included employment of nuclear weapons by the adversary. Defensive in nature, it was to be fought by luring enemy deep into Chinese territory, causing attrition in a gradual manner, trading space for time, characterised by mass employment of regular troops to make up for inferior weapon systems, with heavy reliance on militia forces.

| In pursuit of the ‘People’s War’ Doctrine, Mao went in for limited war against ill prepared India in 1962, to keep the neighbour restrained. Again in 1969, with border tension leading to Ussuri River skirmish (Damanski-Zhenbao Islands), Mao took on President Brezhnev. |

|

Mao’s strategy was a combination of ‘Protraction and Attrition’; implied

diplomatic manoeuvre with the strong and coercion against weak. In 1949, PRC aligned with erstwhile Soviet Union to ward off threat from Japan. In October 1950, PLA marched into Tibet, re-establishing Chinese control to ensure stable periphery. Around the same time, perceiving Mac Arthur’s advance across the 38th Parallel as threat to the mainland, China jumped into the Korean War. In pursuit of the ‘People’s War’ Doctrine, Mao went in for limited war against ill prepared India in 1962, to keep the neighbour restrained. Again in 1969, with border tension leading to Ussuri River skirmish (Damanski-Zhenbao Islands), Mao took on President Brezhnev. By openly challenging Soviet Union, China was able to set stage for reconciliation with America to imbalance the adversary.

People’s War/Local War under Modern Conditions (1979-90)

In February 1979, China launched a massive attack on Vietnam to reassert its control over the latter, in pursuit of its ‘peaceful periphery’ policy. It was in keeping with its aggressive strategy of using force to achieve political objectives. PLA performed poorly which led to review of its doctrine and structures This also coincided with Deng Xiaoping’s ‘four modernisations’ drive launched in December 1978. The new military doctrine-“People’s War under Modern Conditions” was focused on mitigation of threat from the Soviet Union. Earlier concept centred on defence was revised in favour of mobile warfare, with pre-eminence of modern weapons in war fighting. Towards the mid-1980s, with the gradual decline of Soviet Union and change of threat perception, there was again a strategic review, resulting in the formulation of new doctrine of “Local War under Modern Conditions”.

Local War under High Tech Conditions (1991-2004)

The high intensity ‘1991 Gulf War’ and changed international situation were key factors for PLA to initiate major doctrinal reforms during the 1990s. In 1995, the Central Military Commission (CMC) the highest military body put forth ‘New Generation Operation Regulations’ (xin yidai zhuozhan tiaoling) to ‘fight and win future wars’. The two transformations (liangge zhuanbian) sought to make Chinese military undergo metamorphoses; first-from an Army preparing to fight and win ‘local wars under ordinary conditions’ to fight and win ‘local wars under high-tech conditions’ and second-to transform the armed forces from one based on quality to one based on quality. An important component of the new doctrine was the concept of ‘War Zone Campaign’ (WZC)”. More offensive in design; ‘active defence’ being the core element, it encompassed controlled space and time, deployment of Rapid Reaction Forces (RRFs) and combined arms operations.6 It envisioned prosecution of future campaigns under ‘Unified Joint Services Command’ guided by the CMC.

|

Central Military Commission (CMC) the highest military body put forth ‘New Generation Operation Regulations’ (xin yidai zhuozhan tiaoling) to ‘fight and win future wars’. The two transformations (liangge zhuanbian) sought to make Chinese military undergo metamorphoses; first- from an Army preparing to fight and win ‘local wars under ordinary conditions’ to fight and win ‘local wars under high-tech conditions’ and second- to transform the armed forces from one based on quality to one based on quality. |

|

China’s White Papers act as authentic indicators of doctrinal shift since the late 1990s. The first ‘White Paper’ was released in July 1998 titled “China’s National Defence7”. It was for the first time that PRC systematically expounded on its defence policies and explicitly expressed its new outlook on security. Second ‘White Paper’ followed two years later which laid stress on China’s priorities in safeguarding sovereignty and territorial integrity. Another ‘White Paper’ on ‘China’s National Defence’

was released in December 2002 which brought China’s core national interests as the fundamental basis for formulation of the defence policy. The ‘Gulf War 2003’ demonstrated the importance of ‘mechanisation’ and ‘informationisation’. In 2004, President Hu Jintao laid down revised mandate for the military; “to win local wars under informationised conditions”.Consequently, the 2004 ‘White Paper’ propounded the idea of dual historic mission of ‘mechanisation and informationisation’, besides delving on the concept of ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA) with Chinese characteristics8.

Local War under Informationised Conditions (2005 onwards)

The first decade of the new millennium was perceived by the Chinese strategic community as the ‘critical period of multi-polarisation’ leading to the review of national security strategy, dealt in the ‘White Paper’ released in 2006. As per threat assessment by the security experts, probability of full-scale external aggression was unlikely in the near terms. However, in the

future conflicts, the PLA would be faced with technologically superior adversary. Therefore, the idea behind reframing national doctrine from ‘high-tech conditions’ to ‘informationised conditions’ was on the assumption that through informationised conditions, technologically superior adversary could be defeated.

Chinese military doctrine of ‘Local Wars under Informationised Conditions’ has two components. ‘Local Wars’ envision short swift engagements with limited military objectives in pursuit of larger political aim. ‘Informationised Conditions’ refers to the penetration of technology into all walks of modern life, but specific to war fighting includes IT, digital and ‘artificial intelligence’ applications. It implies network-centric environment and waging information operations to ensure battlefield domination. In essence, the aim is to achieve complete security of PLA networks while totally paralyzing that of adversary’s. This encompasses electronic warfare along with psychological warfare and deception to attack enemy’s Command, Control, Communications, Computer, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems, employing both hard and soft kills.

The concept of ‘informationisation’ is broad-based, all-inclusive and gives prominence to information ascendency as the decisive determinant and the key battle-winning factor. Salient operational facets of ‘Limited War under Modern

Informationised Conditions’ include induction of high-tech force multipliers, network centricity, Information Warfare (IW), jointness and interoperability, control of outer space, integrated forward logistics system and ideal man-machine mix.

Decoding – China’s Ways of War Fighting

As evident from the above, the Communist leadership has continuously reviewed the war fighting doctrines in consonance with prevailing security environment. To visualise the future course, it is important to analyse the rationale behind path- breaking military reforms initiated by President Xi Jinping over the last five years. On assuming the mantle of the Fifth Generation leadership in 2012, President Xi unfolded ‘China Dream’ (fixing-restoration) which envisions ‘powerful and prosperous’ China. To translate his ‘China Dream’ into reality, he outlined twin objectives; first to become ‘fully modern economy by 2035’ and acquire ‘great power status by 2049’. President Xi Jinping foresees China to be the key player in shaping the new world order with Chinese characteristics. Alongside stability and economic progress, sovereignty is a glue to foster nationalism. It implies security of periphery and integration of Taiwan and other claimed territories with the motherland, wherein use of force remains an option.

|

The Ninth ‘White Paper’ on ‘National Defence’ published in May 2015 was titled ‘China’s Military Strategy’. Its focus is on building strong national defence and powerful armed forces as a security guarantee for China’s peaceful development. The theme is ‘active defence’ and stress remains on winning ‘local wars under conditions of modern technology’. Priority has been accorded to Navy and Air Force vis-à-vis the ground forces. It also marked a shift in the naval strategy from ‘off shore waters defence’ to combined strategy of ‘off shore waters defence and open sea protection’ to secure its maritime interests. Establishment of ‘Air Defence Identification Zone’ (AIDZ) is in sync with the new strategy. |

|

The sense of urgency with which President Xi Jinping initiated the transformational process could be attributed to the geopolitical considerations – U.S. strategy of rebalancing to Asia-

Pacific being a major factor. The underlying rationale behind the critical reforms was twofold; firstly prepare the military for China’s expanding global role and secondly, establish Party’s firm control over the PLA through the revamped CMC. The Ninth ‘White Paper’ on ‘National Defence’ published in May 2015 was titled ‘China’s Military Strategy’. Its focus is on building strong national defence and powerful armed forces as a security guarantee for China’s peaceful development. The theme is ‘active defence’ and stress remains on winning ‘local wars under conditions of modern technology’9. Priority has been accorded to Navy and Air Force vis-à-vis the ground forces. It also marked a shift in the naval strategy from ‘off shore waters defence’ to combined strategy of ‘off shore waters defence and open sea protection’ to secure its maritime interests. Establishment of ‘Air Defence Identification Zone’ (AIDZ) is in sync with the new strategy.

Salient facets of China’s future was fighting are as under10:-

- Adopt holistic approach to balance ‘war preparation’ and ‘war prevention’, create favourable posture, resolutely deter and ‘win informationised local wars’.

- Respond to multi-directional security threats; adhere to principles

of flexibility and mobility to facilitate concentration of superior forces while ensuring self- dependence.

- Employ integrated combat forces to prevail in system-vs-system operations, featuring information dominance, precision strikes and joint

- Plan for strategic deployment and military dispositions to clearly divide areas of responsibility, with the ability to support each other as organic whole e. reorientate from ‘theatre’ to ‘trans-theatre’ operations.

- Build a modern system of military forces with Chinese characteristics and constantly enhance

- Continue to pursue the strategy of “Nibbling and Negotiating” (yi bian dan, yi bian da -talking and fighting concurrently); case in point, its actions in the South China Sea.

- As part of defence diplomacy, expand military cooperation with major powers and neighbouring countries, for the establishment of regional security framework.

To align the specific services potential with the above strategic direction, salient advances in the armaments are designed to achieve domination in the field of information warfare, anti-radiation missiles, electronic attack drones, direct energy weapons, airborne early warning control system, anti-satellite weapons and cyber army under the ‘Strategic Support Force’11. Even the focus of the Chinese military publications dealing with new modes of war fighting is on jointness and space-based operations. Information based operations are an on-going process, conducted even during the peace time, which could prove a valuable asset during the times of conflict.

|

At the macro level, major changes have been instituted with focus on civil-military integration, jointness and speedy decision- making process. With the redefined role, CMC is now responsible for formulating policies, controlling all the military assets and higher direction of war. |

|

Key Result Areas (KRAs) for the services have been clearly defined in keeping with the higher strategic direction. PLA Army (PLAA) is required to reorient from ‘theatre defence’ and adapt to precise ‘trans-theatre mobility’ missions. PLA Navy (PLAN) while gradually shifting focus to ‘offshore waters defence with open sea protection’ is required to build a combined, multi-functional and efficient maritime force structures. PLA Air Force (PLAFF) in line with the strategic requirements to execute informationised operations is to create requisite structures to ensure transition from erstwhile territorial air defence to building air-space capabilities. Besides it is also expected to boost early warning, air strike, information counter measures and force projection potential.

The ‘Rocket Force’ is adopting transformational measures through reliance on technology upgrades; enhance safety and reliability of missile systems both nuclear and conventional, thus strengthening strategic deterrence. The ‘Strategic Support Force’ is to deal with challenges in the outer space and secure the national space assets. Besides, it is also required to expedite the development of ‘Cyber Force’ by enhancing situational awareness and security of national information networks.

Systems and structures have been revamped across the board. At the macro level, major changes have been instituted with focus on civil- military integration, jointness and speedy decision-making process. With the

redefined role, CMC is now responsible for formulating policies, controlling all the military assets and higher direction of war. As a sequel to the military reforms, the Theatre Commanders directly report to the CMC.

At the operational level, erstwhile 17 odd Army, Air Force and Naval commands have been reorganised into five ‘Theatre Commands’ (TCs); Eastern, Western, Central, Northern and Southern. With all the war fighting resources in each battle zone placed under one commander ensures seamless synergy in deploying land, air, naval and strategic assets in a given theatre. In addition, 84 corps level organisations have been created including 13 operational corps, as well as training and logistics installations. Given the sensitivity of Korean Peninsula and disputed islands territories, the deployment is biased towards Eastern and Northern Theatres. The broad area of responsibility of the reorganised TCs is as under:-

| |

Eastern–Nanjing |

(Taiwan, East China Sea) |

– 71, 72 & 73 Corps |

| |

Southern–Guangzhou |

(Vietnam and South China Sea) |

– 74 &75 Corps |

| |

Western–Chengdu |

(India & Internal Security) |

– 76 &77 Corps |

| |

Northern–Shenyang |

(Korean Peninsula & Russia) |

– 78, 79 & 80 Corps |

| |

Central–Beijing |

(Internal Security & Reserves) |

– 81, 82 & 83 Corps |

China’s naval strategy in the Western Pacific is to counter U.S. aircraft carrier-based assets by concentrating on the nuclear-powered stealth submarines, littoral class surface ships and land-based anti-ship cruise missiles DF-21D ( high precision heavy warhead aircraft carrier killers). It is also known to have deployed DF-26 Missiles, ‘Guam Killer’ with a range of 5500 km. Besides Liaoning, three more aircraft carriers are expected to join PLAN soon. Current fleet of 62 submarines is expected to add another 15 boats in the near future.

To make the armed forces nimbler, a reduction of 300,000 rank and file, mostly from non-combatant positions has been ordered which will downsize the PLA to around to 1.8 million. To support capacity building in pursuit of its envisioned warfighting, adequate budgetary support has been provided with substantial periodic increase in the defence expenditure. The defence allocations for the year 2018 was pegged at $ 175 bn12. (Taking into account the hidden expenditure, the actual figures are much higher).

Conclusion

| President Jiang Zemin had stated – “PRC should first turn itself into a powerful country if it intends to make a greater contribution to progress of mankind and world peace”. The grand strategy of the PLA here on, was based on the key assumption that economic prosperity will afford China greater international influence, diplomatic leverage and robust modern military. |

|

But for China, no other country can claim to link its ancient classics and dictums of strategic thoughts to its present statesmanship. This is evident from the singular uniqueness of PRC leadership, which as a matter of practice, invokes principles of warfare from events dating back to thousands of years. As a result, Its national defence policies are deeply impacted by the nation’s strategic culture.

The Chinese strategic community has continuously reviewed its war- fighting strategies inconsonance with the international security environment, resulting in periodic doctrinal shifts. Mao Zedong, the architect of 1949 Communist Revolution propounded the concept of ‘People’s War’, as major security concern then was the defence of hinterland. As a sequel to the strategic review undertaken towards the early 1980s, it was perceived that while major wars were unlikely, yet China getting involved in the limited local conflicts remained high. Consequently, ‘modern conditions’ was added to ‘People’s War’ doctrine. Large scale restructuring of defence forces was undertaken as part of the ‘Four Modernisations’.

A decade later, given the seismic changes in global arena and technology intensive operations by the US during the ‘1991 Gulf War’ led to China initiating major doctrinal reforms. By the late 1990’s, PLA operationalised the revised doctrine; “Local Wars under High-Tech Conditions”. It is around this time that former President Jiang Zemin had stated- “PRC should first turn itself into a powerful country if it intends to make a greater contribution to progress of mankind and world peace”. The grand strategy of the PLA here on, was based on the key assumption that economic prosperity will afford China greater international influence, diplomatic leverage and robust modern military.

The year 2005 witnessed yet another shift in the Chinese war fighting doctrine as both during the ‘2003 Gulf War’ and Kosovo conflict, importance of mechanisation and informationisation was duly highlighted. Hence, the rationale behind reframing the doctrine from ‘High-Tech’ to ‘Informationised Conditions’ was the conviction of the Chinese strategists that through the ‘Informationisation’ ascendency, it was possible to defeat a technologically superior adversary. Whereas mechanisation was to provide foundation, informationisation was the driving force.

Deep rooted military reforms initiated by President Xi Jinping since 2013 has provided major impetus towards operationalisation of “Local Wars under Informationised Conditions” Doctrine. Focus of ‘Ninth White Paper’ is on winning ‘local wars in conditions of modern technology’. President Xi Jinping commenced his second term in 2018 by exhorting the 2.3 million strong PLA to be combat ready and focus on ‘how to win wars’. He has laid down 2035 as the timeline for PLA to transform into a modern fighting force, at par with Western Armies, fully capable of supporting

China’s global role.

The impact of China’s doctrinal shift and its growing war waging potential is evident from Beijing’s growing assertiveness, in pursuit of its strategic interests. The latest Pentagon Report has sounded alarm on China’s relentless drive for global expansion, both by military and non-military means. PRC is on a spree to acquire string of military bases, especially in the Indian Ocean Region. This will enable PLA to project power to enhance its strategic footprint and emerge as a pre-eminent power in the Indo-Pacific region. As per Dan Taylor, senior US defence intelligence analyst, China is rapidly building robust and lethal force with capabilities spanning the ground, air, maritime, space and information domains, designed to enable Beijing to impose its will in the region and beyond13.

For India the implications are serious given its complex relations with China. While India is not in position to match China’s fast expanding military and economic clout, it is also constrained to join any grouping such as the ‘Quad’ with US, Japan and Australia so as not to antagonise China. Above paradox notwithstanding, India has no option but to revamp its military preparedness and scale up its defence budget to thwart any misadventures as Doklam type of situations could be a new normal. Delhi also has to have its long term policy in place to emerge as an important player in the Indo-Pacific.

In the Chinese concept of ‘Comprehensive National Power’ (CNP), hard power is a key component. Its military culture lays immense emphasis on ‘strategic configuration of power’ to create favourable disposition of forces and exploit asymmetric edge. PRC has set course to emerge as a superpower by the mid of this Century, with its military’s doctrine fully aligned to support the grand design. Hence, it is vital for the global polity particularly the neighbourhood to follow PRC’s war fighting doctrinal developments closely as Communist leadership narrative on nation’s rise to be peaceful-defies its past legacy.

Endnotes

- Liang Hung Lin, (March 2011), Journal of Business Ethics, Volume 99, pp441-51.

- Michael D Swine & Ashley J Tellis (2000), Interpreting China’s Grand Strategy, p59

- Henry Kissinger, (2011), On China, Penguin Books, New York, p23-25.

- Note 3, op cit,

- Mark A Ryan, ( 2016), Introduction to Pattern of People’s War Fighting,

- Personal visit as Defence Attaché in China to 43 Airborne Division at Kaifeng in June

- White Paper China National Defence (July1998), (The author was then Defence Attaché in China and was present when the first White Paper was released by the Director, Foreign Affairs Bureau, PLA).

- White Paper, National Defence (2004),

- White Paper-China’s Military Strategy (May 2015),

- https:// economictimes.indiatimes com. Accessed 16 January 2019,

- Times of India, (17 March 2019), Expansionist China Alarms Pentagon, New