Abstract

Two most powerful organs which are critical for the very survival of current Chinese authoritarian regime are the Communist Party and the Army. The latter historically has been controlled by the Party.The underlying rationale behind the critical reforms were twofold; firstly, prepare the military for China’s expanding global role and secondly, establish Party’s firm control over the PLA through revamped CMC.China has therefore, formulated a long-drawn strategy, with well-defined national objectives. These are stability, sovereignty and modernity i.e. sustained economic development.In this milieu, ‘Stability’ implies unchallenged authority of the CPC and its continuation in power.

Background

Two most powerful organs which are critical for the very survival of current Chinese authoritarian regime are the Communist Party and the Army. While the Communist Party of China (CPC), was founded on 01 July 1921 at Shanghai, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) traces its roots to the ‘Nanchang Uprising’ of 01 August 1927, when stalwarts like Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai revolted against the Nationalist Forces . Both share a unique symbiotic relationship. This historic bonding was formalised in December 1929, at the Ninth Meeting of the CPC convened at Gutian, a town in Fujian Province. During the conference, Mao addressed the men of Fourth Army and clarified the role of military; “to chiefly serve the political ends” .

Thus, absolute control of the CPC over the Red Army became entrenched. Since then, People’s Liberation Army (PLA)has remained the Army of Communist Party and not of the nation. Incidentally, President Xi Jinping visited Gutian on 30 October 2014 to address ‘Military Political Work Conference’. In his speech, he reiterated what Mao had asserted eight and half decades earlier i.e.; “PLA still remains Party’s Army and must maintain absolute loyalty to the political masters” . Traditionally, PLA has been well represented in the apex political policy making bodies. China’s highest defence body, Central Military Commission (CMC) is exclusively composed of senior most military commanders, headed by the President.

PLA played a pivotal role during the Communist Revolution as an armed wing of the Party. Its top commanders namely Mao and Deng emerged as the icons of First and Second Generational leadership. Barely a year after its establishment in 1949, People’s Republic of China (PRC) entered the ‘Korean War 1950-53′ to lock horns with the US-led UN Forces. Suffering over half million casualties, Chinese Forces succeeded in pushing the adversary back to the 38th Parallel, thus restoring ‘status quo ante’. In 1962, PLA convincingly defeated the Indian Army in a limited conflict. However, it performed poorly against the Vietnamese Army in 1979. Here on began the process of restructuring and modernization the PLA.

Defence was one of the ‘Four Modernizations’ enunciated by Deng, to transform China. However, there was lack of strategic direction. In 1993, President Jiang Zemin directed the PLA to prepare for ‘local wars under modern conditions’ on observing the power of Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA) displayed by the US military in the 1992 Gulf War . This paved the way for the initiation of major doctrinal reforms in the Chinese defence forces towards late 1990s. The twin transformations (lianggezhuanbian) were aimed to prepare the PLA to ‘win local wars under high tech conditions’ and facilitate transition from ‘quantity to quality’ based military. In 2004, President Hu Jintao laid down revised mandate for the military; ‘to win local wars under informationised conditions’ .

China has formulated a long-drawn strategy, with well-defined national objectives. These are stability, sovereignty and modernity i.e. sustained economic development. ‘Stability’ implies unchallenged authority of the CPC and its continuation in power.

However, the Process of radical reforms commenced only on president Xi Jinping assuming power as the ‘Fifth Generation’ leader in 2012-13. The sense of urgency could be attributed to the geopolitical considerations; US strategy of rebalancing from West to East, being a major factor. The underlying rationale behind the critical reforms were twofold; firstly, prepare the military for China’s expanding global role and secondly, establish Party’s firm control over the PLA through revamped CMC. The path breaking reform process kick started during the Third Plenum of 18th Central Committee of the CPC held in 2013, with the establishment of National Security Commission (NSC), headed by the President as Chairman. The on-going reform process is deep rooted and goes well beyond the structural changes. Its impact is expected to be wide and varied, having both regional and global implications. The paper undertakes a holistic overview of China’s current military reforms phenomenon, with focus on salient imperatives, doctrinal dimensions, organizational restructuring and strategic ramifications.

Salient Imperatives

The on-going military reforms process is driven by multiple factors. Obama Doctrine of ‘Pivot to Asia’ enunciated in 2011 sought to deploy 60 per cent of US military assets in the Asia-Pacific region by the end of decade lent impetus to China’s military reforms and modernization . Even the Trump Administration has taken a tough stance against the Chinese growing assertiveness in South China Sea. Defence policy makers in Beijing are well aware of the prevailing wide gap in the military capabilities between the US and Chinese armed forces.

Chinese Communist leadership has laid down 2049 as the timeline for the nation to achieve status of ‘developed socialist state’. During the 19th Party Congress held at Beijing in October 2017, President Xi Jinping unfolded his grand design, referring to China entering ‘new era’, advocating greater role in the world affairs . To realise its global ambition, China has formulated a long-drawn strategy, with well-defined national objectives. These are stability, sovereignty and modernity i.e. sustained economic development.

‘Stability’ implies unchallenged authority of the CPC and its continuation in power. Absolute systematic control of the Communist Party over the military remains sine qua non. During the inaugural ceremony of newly constituted ‘Theatre Commands’ on 01 February 2016, President Xi had stated; “Centralisation of military was vital. All the theatre commands and PLA should unswervingly follow absolute leadership of the Communist Party and CMC to the letter” . ‘Sovereignty’ besides external non-interference entails protecting core national interests which encompasses unification of Taiwan with the motherland and exercising control over South China Sea; perceived by Beijing, as its backyard. Lately, Arunachal Pradesh which China claims as South Tibet has also been included in the list of core interests. Diminution of US influence in Asia-Pacific and containing Japan are extended agendas of sovereignty. Nationalists Government gaining power in Taiwan also contributed towards accelerating the military reforms. For the Communist Party to remain in power, ‘economic development’ is the key. Hence, sustaining rapid pace of growth is not an option but imperative for the Chinese leadership. Strong central authority and peaceful periphery are considered essential prerequisites for prosperity and progress.

‘Stability’ implies unchallenged authority of the CPC and its continuation in power. Absolute systematic control of the Communist Party over the military remains sine qua non. During the inaugural ceremony of newly constituted ‘Theatre Commands’ on 01 February 2016, President Xi had stated; “Centralisation of military was vital. All the theatre commands and PLA should unswervingly follow absolute leadership of the Communist Party and CMC to the letter.

Doctrinal Dimensions

Concept of ‘Comprehensive National Power’ (CNP) which includes both hard and soft power is central to Chinese thinking. Acquisition of hard power is seen as a key component towards enhancing nation’s CNP. As per President Xi Jinping, military reforms are the key to realisation of ‘China Dream’ . This is also vital for the implementation of ‘Belt-Road Initiative’ and ‘Maritime Silk Route’ projects. In fact, Chinese military strategic culture lays great emphasis on exploiting propensity of things i.e. ‘strategic configuration of power’-Shi to achieve one’s objectives .The core of strategy is not to fight the adversary, but to create disposition of forces so favourable that fighting is unnecessary, in consonance with Sun Zu’s dictum, “to subdue enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” The on-going military reforms are oriented towards capacity building and force projection.

Concept of ‘Comprehensive National Power’ (CNP) which includes both hard and soft power is central to Chinese thinking. Acquisition of hard power is seen as a key component towards enhancing nation’s CNP. As per President Xi, military reforms are the key to realisation of ‘China Dream’.

The general trend of the Chinese strategic thinking is defined in the White Papers on National Defence issued periodically since 1998. The theme of ‘Ninth White Paper’ published in May 2015 titled ‘China’s Military Strategy’, was ‘active defence’, with stress on winning ‘local wars in conditions of modern technology .The thrust was on expounding maritime interests, priority being accorded to navy and air force vis-à-vis the ground forces.

Chinese military doctrine of ‘Local Wars under Informationised Conditions’ has two components. ‘Local Wars’ envision short swift engagements with limited military objectives in pursuit of larger political aim. ‘Informationised Conditions’ refers to the penetration of technology into all walks of modern life, but specific to war fighting which includes IT, digital and artificial intelligence applications. It implies network centric environment and waging information operations to ensure battlefield domination. In essence, aim is to achieve complete security of PLA networks while totally paralyzing that of adversary’s. This encompasses electronic warfare including computer networks, psychological warfare and deception to attack enemy’s C4ISR systems, employing both hard and soft kills . Joint operations and integrated logistics are inherent components of the doctrine.

Thrust Areas

The main thrust of the on-going military reforms is on revamping the systems and structures across the board, at all levels i.e. political, strategic and operational. At the macro level, major changes that have been instituted are about deepening national defence through military reforms with Chinese Character, in keeping with the guidelines issued by the CMC. The focus is on civil-military integration to achieve unity of command, joint operations and optimization. The composition of the CMC itself has been balanced out to eliminate erstwhile ground forces bias. With the redefined role, CMC will now be responsible for formulating policies, controlling all the military assets and higher direction of war. As a sequel to the military reforms, PLA, People Armed Police Force (PAPF) and Theatre Commanders directly report to the CMC.

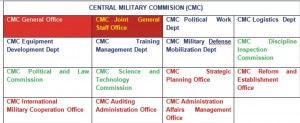

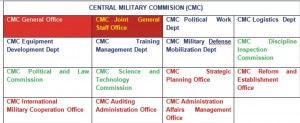

The erstwhile PLA Headquarters had four key Departments-General Staff, Political, Logistics and Armament. These have been reorganized and integrated into the restructured CMC, ensuring centralised control at the highest level. In the new set up, there are fifteen bodies. These include five departments and three commissions besides seven offices .(diagram below refers). With the integrated Joint General Staff under the CMC, the decision-making process at the apex level has been streamlined. In the restructured CMC, President as the Commander in Chief now exercises direct operational control over the military through the ‘Joint Operational Center’.

Besides the existing PLA Navy (PLAN) and PLA Air Force (PLAFF) Headquarters, three new Service Headquarters have been created. These are ‘Ground Forces Command’ making it a service, Rocket Force-an upgrade of Second Artillery which operates both strategic as well as conventional missiles and ‘Strategic Support Force’ to control as also secure cyber and space assets. These structural additions will greatly facilitate prosecution of ‘Informationised Local Wars’.

At the operational level, erstwhile 17 odd army, air force and naval commands have been reorganized into five ‘theatre commands'; Eastern, Western, Central, Northern and Southern. With all the war fighting resources in each battle zone placed under one commander will ensure seamless synergy in deploying land, air, naval and strategic assets in a given theatre. In addition, 84 corps level organizations have been created including 13 operational corps, as well as training and logistics installations. To make the armed forces nimbler, a reduction of 300,000 rank and file, mostly from non-combatant positions has been ordered which will downsize the PLA to around to 1.8 million.

Theatre Commands (TCs) – Deployment of Corps

- Eastern TC– Nanjing (Taiwan, East China Sea)- 71,72&73 Corps

- Southern TC-Guangzhou (Vietnam and South China Sea)- 74 &75 Corps

- Western TC-Chengdu (India &Internal Security)-76 &77 Corps

- Northern TC– Shenyang (Korean Peninsula & Russia)- 78,79&80 Corps

- Central TC– Beijing (Internal Security& Reserves)- 81,82&83 Corps

Capacity Building

Salient advances in the armaments are designed to achieve domination in the field of information warfare, anti-radiation missiles, electronic attack drones, direct energy weapons, airborne early warning control system, anti-satellite weapons and cyber army under the Strategic Support Force[i]. Even the focus of the Chinese military publications dealing with new modes of war fighting is on jointness and space based operations. Information based operations are an on-going process, conducted even during the peace time, which could prove a valuable asset during the times of conflict.

In consonance with the strategic direction, KRAs for the services have been clearly defined. PLA Army (PLAA) is required to reorient from ‘theatre defence’ and adapt to precise ‘trans-theatre mobility’ missions. This entails elevating capability through restructuring in undertaking multi-dimensional, joint offensive and defensive operations. PLA Navy (PLAN) while gradually shifting its focus from ‘off shore waters defence’ to a combined strategy of ‘offshore waters defence with open sea protection’ is required to build a combined, multi-functional and efficient maritime force structures. It has been tasked to enhance capabilities for strategic deterrence, counter attack, joint operations at sea and provide comprehensive support. PLA Air Force (PLAFF) in line with the strategic requirements to execute informationised operations is to build requisite structures by shifting focus from erstwhile territorial air defence to building air-space capabilities. It is also in the process of boosting strategic capabilities for early warning, air strike, information counter measures and force projection[ii].

[i]Zi Yang (24 January 2018), Ideology behind China’s Fast-Changing Military, The Diplomat. http://thediplomat.com/2018/01/the-ideologu-behind-china’s-fast-changing-military

[ii]Note 11, op cit.

President Xi is the lead architect of the current phase of the path breaking reforms. His ideology which has been enshrined into the Party constitution during the 19th Party Congress also encompasses army rebuilding. It expects PLA to “Obey the Party, be able to win wars and maintain good conduct”. The supreme Commander has also pronounced three tenets for a strong military i.e. confidence, competence and commitment

The Rocket Force to be lean and effective will be adopting transformational measures through reliance on technology upgrades, enhance safety and reliability of missile systems-both nuclear and conventional, thus strengthening strategic deterrence. Strategic Support Force will deal with challenges in the outer space and secure the national space assets. Besides, it will also expedite the development of “Cyber Force” by enhancing situational awareness, cyber defence and security of national information networks. People’s Armed Police Force (PAPF) is to undertake multiple and diversified tasks including contingency tasks under informationised conditions.

President Xi is the lead architect of the current phase of the path breaking reforms. His ideology which has been enshrined into the Party constitution during the 19th Party Congress also encompasses army rebuilding. It expects PLA to “Obey the Party, be able to win wars and maintain good conduct”[i].The Supreme Commander has also pronounced three tenets for a strong military i.e. confidence, competence and commitment. Unlike his immediate predecessors, Xi has maintained close relations with the armed forces, obvious from his frequent appearances at PLA events and visits to remote military bases in various parts of the country. The process is being supported by requisite budgetary allocations; evident from the fact that 2017 defence budget of $151 bn (actual spending estimated to be far higher) marks an increase of over 7 per cent[ii].

Strategic Implications

The on-going China’s military reforms as a phenomenon are possibly one of the biggest generational shake of its kind. Steered by President Xi as the Chairman of the CMC, these radical reforms are in line with the PRC’s envisioned future role as a global player. Although the framework of reforms does not follow traditional Western model or template, yet these are in sync with the key trends in modern warfare. While the primary aim is to scale up national defence capability with Chinese characteristics, the process is geared to serve multiple objectives, with far reaching ramifications.

Domestically, predominance of the Party over PLA stands revalidated with centralization of power structure under the reorganized CMC. By ensuring implicit obedience and absolute loyalty of the armed forces through rejigged structures and reshuffles in the PLA hierarchy, President Xi has reinforced unity of command; most critical for any professional war fighting organization. Total control over the military has ensured that reformed PLA is resistant to the external influences. Xi’s emergence as an unquestionable leader with titles such as the ‘paramount leader’ and Zhu Xi (Chairman) puts him in the league of Mao and Deng. As per the Chinese public opinion, Mao made China great, Deng made it rich and Xi is striving to make it strong. Described as a person with ‘an iron soul’ by former statesman late Lee Kuan Yew, Xi is expected to pursue his stated vision relentlessly.

From the external perspective, exponential accretion in China’s military capability is a cause of concern, particularly in PRC’s neighbourhood. Beijing is already seen to be more assertive towards realising its national objectives. It will be rather naïve to believe that the ‘Belt- Road’ and ‘Maritime Silk Route’ projects are only driven by economic considerations. In fact, these are path breaking initiatives to facilitate China to enlarge its strategic footprint, an essential pre-requisite for the global superpower in making. Communist leadership’s repeated claims that China’s rise will be peaceful,bely its actions on the ground. After all, ‘a dragon remains a dragon’. As per Trump Administration Security Strategy, China and Russia are its main rivals. As Washington is expected to play a greater role in protecting its interests besides assuaging the concerns of its allies and partners in the Asia-Pacific, the region is set to be the scene of intense inter- power rivalry.

Being India’s biggest neighbour with disputed border, clashing geostrategic interests and complex relations, China’s critical military reforms and rapid build-up of its military potential are stark realities which cannot be wished away. It is a matter of serious security concern. From the strategic perspective, India’s current higher defence organizational structure is service specific, lacking integration and jointness. We are yet to formulate comprehensive National ‘Limited War Doctrine’. Due to bureaucratic gridlocks, the procurement procedures of armament and equipment are rather tenuous, proving to be major impediment in modernization process. Current piecemeal and knee jerk approach to augment the defence capability needs to be replaced by long term national defence policy. Restructuring of the higher defence organization to meet the emerging security challenges is no more an option but an imperative.

[i]Note 14 op cit.

[ii]Michael Martina, Ben Blanchard (05 March 2017) Economic News

Being India’s biggest neighbour with disputed border, clashing geostrategic interests and complex relations, China’s critical military reforms and rapid build-up of its military potential are stark realities which cannot be wished away. It is a matter of serious security concern.

In operational terms, before the current reforms, it was PLA’s Chengdu and Lanzhou Military Regions which were responsible for operations against India’s Eastern and Northern borders. Post reorganization, it is now the Western Theatre with integrated Army, Air Force and Rocket Force assets, under a single commander that faces own four army commands (Northern, Western, Central and Eastern) and three air force commands (Western, Central and Eastern). This configuration will pose enormous coordination challenge in the event of a major conflict. Even during the 1962 War, China had constituted single Headquarters for controlling operations in Ladakh and Arunachal (then NEFA) while we fought isolated battles even within the theatre. Ironically, five and half decades on, we remain oblivious to this glaring short coming.

China has avoided major military confrontation since 1979. However, it has cleverly pursued the strategy of ‘nibbling and negotiating’ (yibiandanyibian da-talking and fighting concurrently). Doklam type stand-offs or confrontations in South Sea are part of this strategy and ought to be accepted as the new normal in dealing with PRC. Frequent incursions by the Chinese and hardening claims to Arunachal which it claims as South Tibet need to be seen in the light of the above realities. To realise Xi’s ‘China Dream’, Beijing does not enjoy the luxury of indulging in a major conflict. Therefore, while probability of a major confrontation between the two giants remains low, local skirmishes cannot be ruled out, especially in the contentious locations. As limited engagements demand speedy deployment and a flatter logistics chain, inadequate infrastructure in the border areas stands out as a major constraint for India while the adversary has a distinct edge. This shortcoming needs to be addressed on the highest priority.

China’s critical military reforms and rapid build-up of its military potential are stark realities which cannot be wished away. It is a matter of serious security concern. From the strategic perspective, India’s current higher defence organizational structure is service specific, lacking integration and jointness.

The revolutionary military reforms initiated under the current Chinese Communist leadership are indeed of monumental nature. With President Xi all set to be at the helm well beyond his stipulated two terms i.e. 2023, the military reforms process will continue till 2035, the timeline laid by him for PLA to ‘emerge as a modern fighting force capable of winning wars’. Incidentally, today China faces no external threat and its main security concerns are internal. Continued maintenance of CPC’s unchallenged hold over the system being prime concern of the Communist Leadership, PLA’s identity as the ‘military of the Party’ remains sacrosanct. To further its aspiration as emerging superpower, China’s Military reforms aim to enhance nation’s war waging capacity and power projection capabilities.

The PLA transformation process, its magnitude notwithstanding, is on the fast track. It will take a few decades before the Chinese Armed Forces as a modern military can stake claims to be at par with the Western Armies. PLA undoubtedly is poised for a ‘Great Leap’; in the process set to seriously disrupt the existing ‘balance of power’ dynamics. In the Chinese strategic lexicon, military strength is an important component of the CNP. The global strategic community will constantly struggle to decode the intent of Chinese Leadership; as to how it will deploy exponential accretion in country’s military potential.

Endnotes

[1]Edgar O’Ballance, (1962), The Red Army of China, Faber and Faber, London, p38

[1]David Shambaugh (1996), Soldier and State in China in Brain Hook, The Individual and State, Oxford, New York, p108.

[1]China Military Online, (3 November 2014), Party Controls Gun.

[1]Andrew Scobell, (2004), Chinese Army Building in the Era of Jiang Zemin, University Press of Pacific, p11.

[1]Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, Travis Tanner, Assessing the People Liberation Army in the Hu Jintao Era, Strategic Studies Institute-US War College Press, p10.

[1]President Obama address to Australian Parliament (17 November 2012), Parliament House Canberra, Australia http://www.white house.gov/the-press-office/2011/11/17/remarks-president-obama-australian parliament. Accessed 24 January 2018, 4pm.

[1]Mark Moore,(24 October 2017), New York Post, New York.http://mypost.com, accessed 20 January 2018, 10am

[1]The Hindu, (03 February), China Revamps Military Command Structure

[1] Ibid

[1]Thomas G Mahnken, (2011), Secrecy and Stratagem: Understanding Chinese Strategic Culture, Lowy Institute of international Policy, Australia, p18.

[1]White Paper on China’s Military Strategy (May 2015), The State Council Information Office, People Republic of China, Beijing.

[1]Zi Yang (24 January 2018), Ideology behind China’s Fast Changing Military, The Diplomat.http://thediplomat.com. Accessed 28 January 2018

[1]Business Insider, (14 January 2016), China’s Latest Military Reform Reveals its Rising Ambitions.

[1]Zi Yang (24 January 2018), Ideology behind China’s Fast-Changing Military, The Diplomat. http://thediplomat.com/2018/01/the-ideologu-behind-china’s-fast-changing-military

[1]Note 11, op cit.

[1]Note 14 op cit.

[1]Michael Martina, Ben Blanchard (05 March 2017) Economic News